The past week was packed with new data releases which sent some mixed signals on the health of the UK economy and the prospects for 2026. This note takes stock.

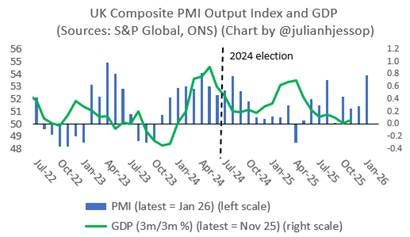

The most encouraging news came from the latest S&P Global Flash UK PMI Composite Output Index, which jumped to 53.9 in January from 51.4 in December. This was the highest reading since April 2024 and suggests that growth is accelerating again after stalling in the final quarter of last year.

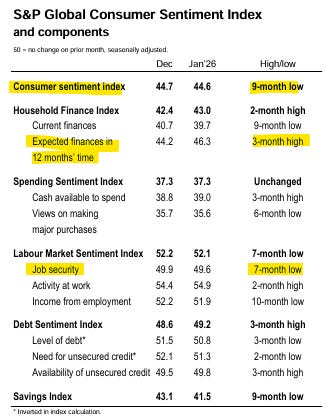

There were some positive signs in the January surveys of consumer confidence too.

The latest GfK survey showed that households are still gloomy about the prospects for the economy as a whole, but this has been a consistent feature of this poll for at least a decade.

More interestingly, sentiment on the outlook for personal finances is relatively upbeat and continuing to improve. Hopes of lower inflation and further interest rate cuts appear to be offsetting fears over jobs and taxes.

However, some other news was not as well received.

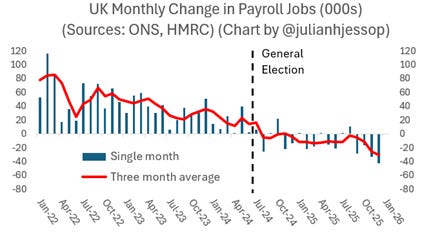

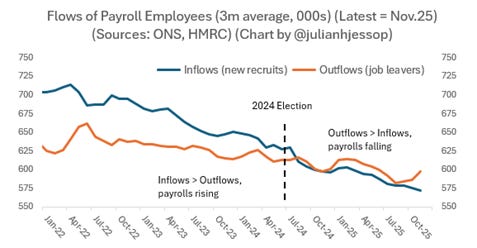

For a start, the labour market continues to weaken, with initial estimates from PAYE data suggesting a net loss of another 43,000 payroll jobs in December.

The boost to incomes from rising wages is also fading. The ONS data showed that regular pay growth in the private sector slowed from 3.9% to 3.6% in the three months to November.

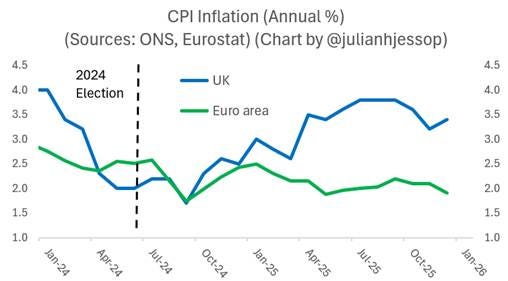

Meanwhile, the CPI measure of inflation accelerated again in December, from 3.2% to 3.4%. This pick-up was largely expected (due to base effects in tobacco duties and air fares), but still unwelcome. As my next chart shows, UK inflation continues to relatively hot.

Together, these releases suggest that the recovery in real incomes – a key driver of the pick up in retail sales volumes last year – is petering out.

UK inflation is still likely to fall to around 2% in April as regulated prices rise by less than in 2025. However, underlying cost and price pressures remain sticky, and medium-term inflation expectations are too high for comfort.

Finally, other business and consumer surveys were mostly downbeat.

Like the GfK poll, the S&P Global UK Consumer Sentiment Index reported an improvement in sentiment towards future finances. But otherwise it was still weak, with “job security” continuing to worsen.

The latest CBI surveys covering Industrial Trends and Distributive Trades were both gloomy too, with investment and hiring intentions subdued.

Finally, to go back to where this piece started, the detail of that upbeat PMI was less promising. Underlying cost and price pressures remain strong, and job losses still appear to be accelerating.

Overall, there is too little evidence to conclude that the UK economy has “turned the corner”. It is more likely that we are simply witnessing a temporary improvement in sentiment at the start of a new year. This might support a bounce in activity in the spring as Budget uncertainty continues to recede, but there are plenty of reasons to doubt that this would be sustained.

Indeed, some of the recent news has illustrated the downside risks that I summarised in an earlier preview of the outlook for 2026.

One is that the hoped-for falls in inflation and especially in interest rates may fail to materialise. Here, the pick-up in both activity and price pressures in the PMI survey increases the chances the Bank of England will leave rates on hold at the next MPC meeting in early February.

The persistent weakness in the labour market is a concern too.

To be clear, the underlying picture is not as bad as some headlines suggest. The rise in the unemployment rate is still driven primarily by an increase in the number of people choosing to look for work (a welcome fall in “economic inactivity”), rather than large scale job losses.

Similarly, a closer look at the HMRC PAYE data suggests that the fall in payroll jobs primarily reflects a lack of hiring, rather than more firing (as the chart below shows). In other words, rather than many more people losing their jobs, leavers are not being replaced and fewer new jobs are being created.

This might explain why consumer confidence has been fairly resilient – people who already have a job might still be feeling comfortable.

It may also be that some firms are simply postponing hiring until the economic outlook is a little clearer. This might then lead to a bounce in recruitment in the Spring.

However, the lack of job creation is still a “bad thing”. There is a clear risk too that some firms are postponing firings in hope of a recovery that fails to materialise. The jury is still out here.

But recent developments have surely reinforced worries about the political backdrop, both at home and abroad. President Trump’s increasingly wild tantrums are a clear and present danger in many ways, including to asset prices and business confidence (which both dived last April when he launched his global tariff wars).

Unfortunately, the UK has not become the haven of political stability that many hoped when the Labour government was elected. The so-called “grown-ups” are lurching from one U-turn to another, and the Prime Minister’s position looks increasingly vulnerable.

The Spring Statement and new OBR forecasts in March, even without a formal assessment of the performance against the fiscal targets, could also reignite concerns about yet another round of tax increases in the Autumn Budget (especially if this might be delivered under new management).

The latest news on the public finances was mixed. Borrowing was a bit lower than expected in December. However, the current budget deficit (which is supposed to be eliminated by 2030) was still £94.9 billion in the first nine months of the financial year, just £1.6 billion less than in the same period in 2024-25.

One last caveat is that averages conceal wide differences.

In particular, the improvement in the PMI was heavily dependent on financial services and tech, including new investments related to AI, with many other (more labour-intensive) sectors continuing to struggle. The composite index also does not cover construction (where the separate PMI has been much weaker), or retail.

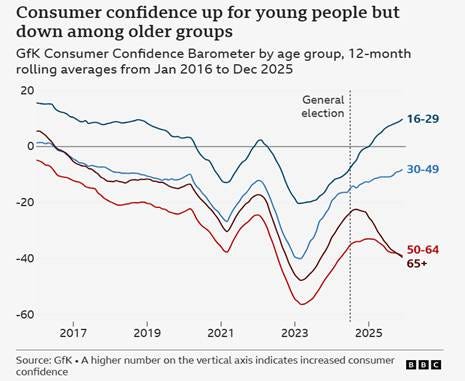

There is also a lot going on beneath the surface in the surveys of consumer confidence. All the major polls now show an unusual divergence between younger and older people, as flagged in this thoughtful piece by the BBC’s Faisal Islam.

This divergence might simply reflect political biases – younger people are more likely to feel positive with a left-leaning government. But I prefer to focus on the economics.

As Kallum Pickering has explained on X, younger people tend to be “asset poor” and therefore more sensitive to shifts in real incomes, where the recent news has been relatively good.

In contrast, older people tend to be wealthier and therefore more sensitive to shifts in asset prices, and they are big savers. Their confidence can therefore be undermined by falls in real house prices or by cuts in interest rates.

More speculatively, I would add that older people may also be more aware of the bigger economic picture, as they are more likely to manage a business or pay large and increasing amounts of tax.

In short, caveats abound. A few “green shoots” have hinted at a post-Budget bounce at the start of 2026. But there have also been some signs of persistent weakness, notably in the labour market, and confidence remains fragile.

ps. you can follow me on X (formerly Twitter) @julianhjessop and on BlueSky.

I also post regularly on Substack