The UK interest rate decision this week is finely balanced – so much so that I was not even sure which way I would vote. Nonetheless, over the course of writing this piece I have persuaded myself to switch to ‘no change’, even though the actual decision is still likely to be a cut.

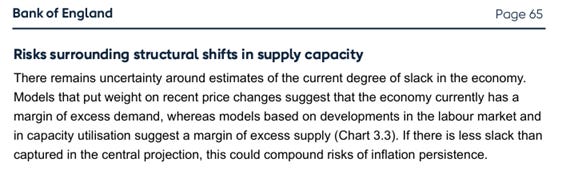

This paragraph from the November Monetary Policy Report (MPR) neatly sums up the MPC’s dilemma.

In short, do you go with the recent inflation data which suggest that there is excess demand and leave interest rates on hold? That is the position taken by many sensible economists, including Andrew Sentance, Liam Halligan and Jagjit Chadha (“Time to make doves cry”).

Or do you put more weight on the weakness of the activity data which suggest there is excess supply and cut rates again to boost demand? That is the view of other equally sensible economists, notably Gerard Lyons (“The Bank of England must be bold”) and, it seems, many in the City.

Perhaps unhelpfully (like Harry Truman’s ‘two-handed economist’!) I could argue this either way.

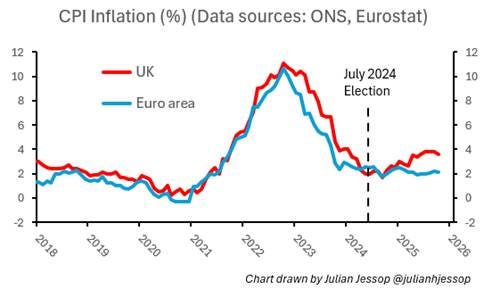

For a start, the fact that headline inflation is currently well above the MPC’s 2% target (at 3.6% in October) is not decisive. Monetary policy is supposed to be forward-looking and the MPC’s mandate (you can read it here) allows members to see past deviations from the target if they are expected to be temporary.

The UK is now an outlier on inflation, especially compared to the euro area, largely reflecting government policy choices which have added to business and household costs. In other words, this inflation is more cost-push than demand-pull, so higher interest rates may not be the answer. But this could still justify keeping interest rates higher for longer if it is feeding into higher inflation expectations and affecting future decisions on wage and price setting.

The evidence here is frustratingly inconclusive. For example, the Bank of England’s latest quarterly survey of public attitudes to inflation suggests that expectations are cooling, but are probably still too high for comfort.

There are mixed signals too from the recent pay surveys. For example, the latest KPMG and REC UK Report on Jobs found that permanent starting salary inflation was the fastest in five months, despite the weakness in hiring activity.

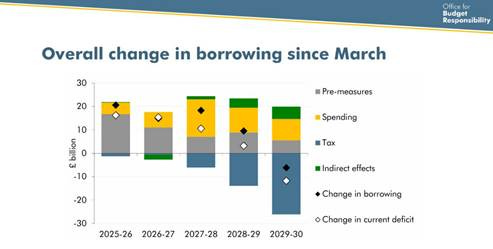

The fallout from the November Budget does not provide a clear steer either. Obviously, pre-Budget speculation killed growth. But the Budget itself may not have been as tight as feared, especially in the early years (the tax increases were backloaded towards 2028 and 2029).

It may therefore be worth waiting for more evidence on whether the easing of uncertainty is enough to kickstart growth. However, the first post-Budget surveys are not encouraging. For example, the S&P Global UK Consumer Sentiment Index showed a further deterioration in confidence in December, especially on future finances and job security.

There are still some key figures between now and the vote on Wednesday, notably the latest labour data and PMI surveys (Tuesday) and inflation (on Wednesday itself). These could tip the balance either way.

Tactically, there are decent arguments on both sides too (sorry!).

The markets now expect a cut, so that would be the easier option. But a short delay until the next meeting (in the first week of February) could boost the MPC’s anti-inflation credibility and allow more time to assess the outlook for 2026.

Last but not least, the monetary data are not decisive either. Broad money growth is running at annual rates of around 4-4½%, which is neither obviously too strong nor obviously too weak.

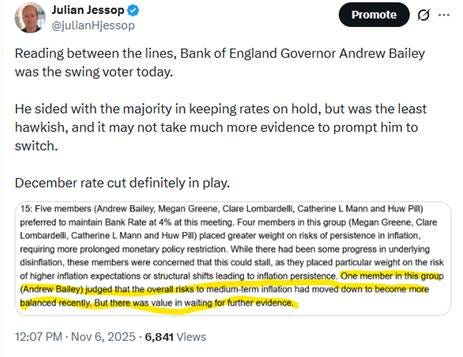

So, what to expect when the decision is announced on Thursday? As I noted last month, the Governor will probably be the ‘swing voter’ again.

Indeed, this is a fundamental feature of the system – as explained below and here, the Governor recommends the decision that he believes will command a majority and has the deciding vote.

I suspect there will now be just enough evidence to prompt Andrew Bailey to switch this month, making the vote 5-4 for a cut. Indeed, the Governor’s steer might be sufficient to persuade one or two others to switch too.

To be clear, though, this would only be because the rapid deterioration in the economy and especially the jobs market is offsetting worries about inflation. This is nothing to cheer.

Despite this, I would now vote for ‘no change’ this week. The MPC’s job is to worry about inflation, not to bail out a government which has no growth strategy of its own.

The current level of interest rates, at 4%, is probably at the top end of a neutral range of 3-4%, rather than being overly restrictive (even allowing for the additional drag from Quantitative Tightening).

In any event, the MPC should ignore the small and temporary fall in headline inflation resulting from measures announced in last month’s Budget, which will simply switch some costs from household bills to general taxation. If the government really wants to make the MPC’s job easier, it should focus on improving the supply-side performance of the economy.

Instead, my preference would be to wait until February and then – if the new evidence permits – resume the policy of cutting rates gradually alongside each quarterly Monetary Policy Report. Cuts in early February and late April would take official rates to 3½%. Hopefully, this would be as low as they have to go.

Ps. added Tuesday 16 December

In the event, this morning’s data has only muddied the waters further!

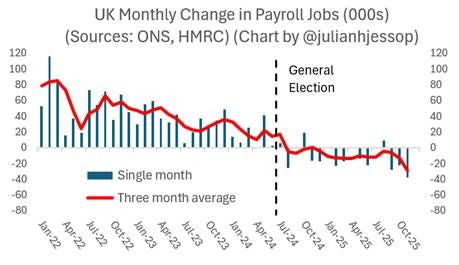

The labour market data were weak, but this was as expected. The relatively reliable HMRC PAYE data show that the pace of job losses has picked up again in the last three months, with 171,000 fewer payrolled employees this November than a year ago. Rising costs and Budget uncertainty are clearly to blame.

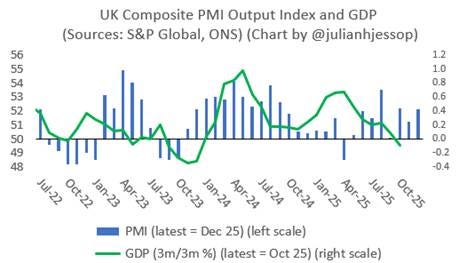

However, the flash UK PMI Composite Output Index picked up to 52.1 (November 51.2). This is at least consistent with hopes that the UK economy will avoid recession as Budget uncertainty eases, but with three important caveats.

First, the composite PMI does not include construction, retail or smaller businesses in sectors like hospitality – all areas where activity is probably much weaker.

Second, it will take some time before any recovery feeds through to jobs – the PMI shows employment continues to fall.

Third, input and output inflation both picked up, underlining the dilemma facing the MPC this week.