I’ve finally found time to review the NBER Working Paper which claims that Brexit has reduced UK GDP by as much as 8% since the vote to leave in 2016. As Martin Wolf writes in today’s Financial Times, “if this is even roughly correct, Brexit has been nothing short of an economic disaster”. But I think it is almost entirely wrong, and here’s why.

Just to be clear, the NBER paper is a serious piece of work by serious economists. It would also be odd to insist that Brexit has had no negative effects at all. But it is entirely reasonable to debate both the magnitude and the duration of these effects, especially when the estimates presented here are so extreme.

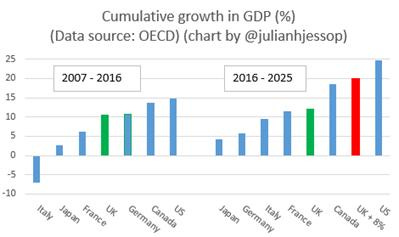

At first sniff, then, the 8% figure fails a simple ‘smell test’. For context, the UK economy has grown by about 12% since 2016, outpacing Japan, Germany, Italy and France. If you add another 8% the UK would have been the fastest growing economy in the G7 – bar only the US – and left its EU peers far behind. This would not be impossible, but it is surely unlikely.

So, how did the authors of the NBER paper arrive at an 8% hit?

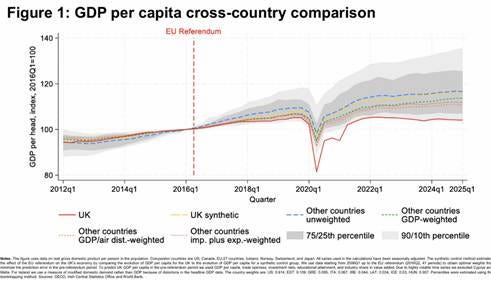

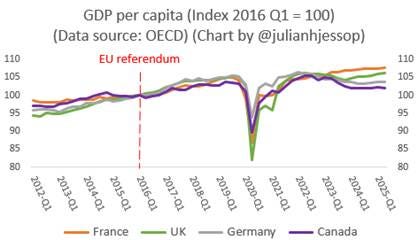

They’ve compared the UK’s per capita GDP growth since 2016 to a wide range of other countries and assumed any underperformance must have been due to Brexit. This chart looks like a disaster, right?

But the choice of comparators still matters. The NBER paper essentially uses two approaches. One is to compare the performance of the UK to some average of a very large group of other economies with whom it may have little in common.

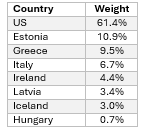

The other approach is to leave the judgement entirely to a computer programme. Synthetic control models use an algorithm to find the weighted group of countries (or ‘doppelgänger’) whose performance was closest to that of the UK before Brexit.

This control group can be a very odd bunch. Indeed, here are the weights in the NBER doppelgänger (note the paper wisely uses a measure of modified domestic demand for Ireland, rather than GDP, though these data are still not strictly comparable).

Now, I know that’s “just what the computer says”. But this group is a strange mix of the US economy (which dominates any GDP-weighted measure) and a host of much smaller countries with special factors of their own. None of these are obvious benchmarks for the UK. Where, in particular, are Germany and France?

More fundamentally, the best fit in one period and in one set of circumstances may not be the best in another, especially where there have been many shocks (not just Brexit) which could be expected to hit the UK differently from other countries (notably Covid and the energy crisis).

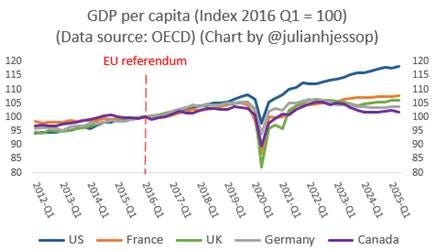

I have therefore done my own version of the NBER chart. This confirms that the real outlier over this period was the US. In per capita GDP terms, the UK has marginally underperformed France and marginally outperformed Germany, which are more obvious benchmarks. And there is no sign of an ‘8%’ hit here.

This picture is clearer if you exclude the US from the chart altogether. (Over this period the US has benefited from low energy prices, a large fiscal stimulus, and the AI boom.)

Note also that Canada is the G7 laggard on per capita GDP, not the UK (or even Germany). That perhaps has something to do with Canada’s very high levels of net immigration – a features shared with the UK. That issue is surely worth discussing further, especially if you are relying heavily on per capita GDP data. But the NBER paper barely mentions migration at all (and then only with a narrow focus on net migration from the EU).

The NBER paper also claims that UK employment would be as much as 4% higher without Brexit. Again this is not impossible but, as the unemployment rate has averaged little more than 4% since 2016, this would have required an implausibly large fall in economic inactivity to fill those jobs.

I am more sympathetic to what the NBER paper says about the costs of the disruption and uncertainty caused by Brexit, especially the impacts on smaller firms and on business investment generally.

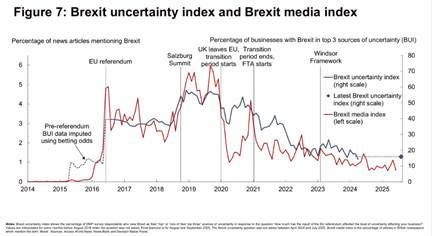

But this uncertainty has now eased – as the paper’s own chart here shows…

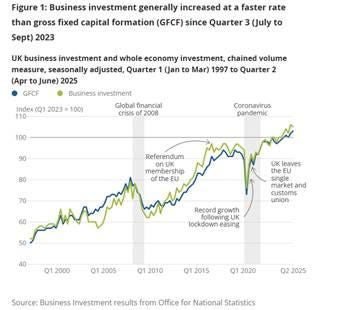

Moreover, business investment has already started to recover (and again, the UK is no longer an outlier compared to peers such as Germany and France).

In summary, my take is that the NBER paper is heavy on data and prior assumptions, but light on commonsense! Nonetheless, it is a well written summary of the mainstream views on the economic impact of Brexit – and I would encourage you to judge for yourself by reading it here.

Ps (added Tuesday 25 November)

I’ve also been asked specifically about the impact of Brexit on UK trade.

It will be interesting to hear what the OBR actually says on Brexit tomorrow (Wednesday 26 November), but my take is that overall UK trade is holding up much better than the OBR and many others had feared)

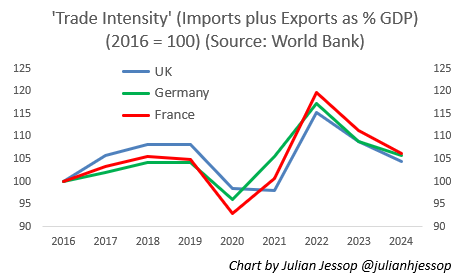

Remember that, as part of its assessment of the impact of Brexit on productivity over the longer term, the OBR has assumed that the volume of UK imports and exports will both be 15% lower than if we had remained in the EU. This covers total trade, both goods and services, and with the whole world, not just the EU.

Falls of 15% had always looked pessimistic given the relatively favourable tariff terms in the initial UK-EU trade deal. And in reality, the overall ‘trade intensity’ of UK GDP has continued to track that of our peers in the EU, rather than collapsed.

The UK has underperformed in trade in goods, and some part of this may be due to the increase in trade frictions with the EU after Brexit (it would be odd if these had no effect).

Nonetheless, this has largely been offset by the UK’s outperformance in trade in services.

At most, the data suggest that the UK’s trade intensity might be a few percentage lower as a result of Brexit – but certainly not 15%.

Such a small change is unlikely to have any significant impact on productivity over the longer term in an advanced economy, such as the UK, which will remain relatively open.

Moreover, any drag is likely to fade over time as businesses adjust, the full benefits of new post-Brexit trade deals start come through, and the EU economies continue to underperform against the rest of the world.

In short, I think the OBR should now be less pessimistic about the impact of Brexit via the trade channel, not more!