The Chancellor has confirmed that the date of the Autumn Budget will be Wednesday 26 November. This is relatively late, raising fears that a longer period of speculation and uncertainty will undermine confidence even further, but there are always trade-offs. I can think of five reasons why waiting might make sense.

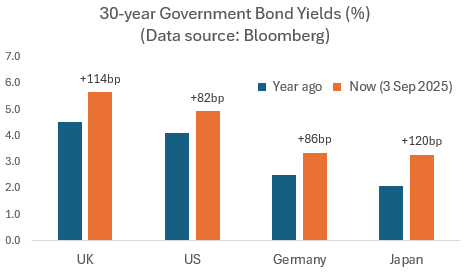

First, and perhaps most obviously, the delay leaves more time for global bond markets to calm down. The surge in 30-year gilt yields over the last year at least partly reflects an international trend. In fact, the increase (in basis points) has been even larger in Japan than in the UK.

Correspondingly, a recovery in sentiment in global markets could still help gilt yields to fall back in time for the Budget, even if the UK remains an outlier (in terms of bond spreads).

Of course, this could also work in the opposite direction if there is more bad news from elsewhere. This might come from the US (for example, higher tariffs could finally feed through into consumer price inflation, exacerbating the tensions between Trump and the Fed), or from France, or half a dozen other countries where concerns about fiscal sustainability are also growing.

Fortunately, then, an improvement in global sentiment is not the only potential upside from having a late Budget.

The second positive is that the UK Government would have more time to find some new savings on the welfare bill to replace the £6 billion or so which has been lost to the U-turns on working-age benefits and on winter fuel payments. These savings would presumably still have to be acceptable to Labour MPs, but the Government would have longer to get the politics right.

Third, and perhaps even more importantly, the Government will have extra time to persuade the OBR that the planned increases in public investment and supply-side reforms will boost the productive potential of the economy.

Interestingly, the OBR has left the door open here. In the Forward to the March EFO, which accompanied the Spring Statement, the fiscal watchdog noted that

“We were unable to incorporate most of the supply-side impacts of these policies in our economy forecast due to insufficient information from the Government on the policy details and analysis of their likely economic effects. We were not, in the limited time available, able to develop our own analysis. We will therefore incorporate an estimate of these impacts in our next forecast.”

This is crucial because, as it stands, the risk is that OBR will downgrade the longer-term forecasts for production and growth. This could easily add more than £10 billion to the ‘black hole’.

However, the OBR also said it might reassess other aspects of the Government’s plans, including those on welfare spending, which could still be bad news.

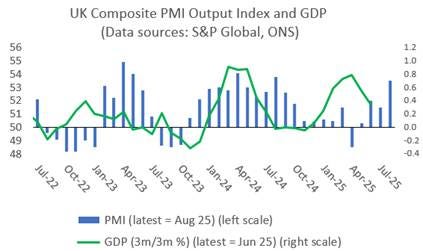

Fourth, there will be more time for some better news on the UK economy. Indeed, there are already a few encouraging signs in the business and consumer surveys, and on underlying price pressures.

For example, the final UK composite PMI for August (covering services and manufacturing) has just been revised up to 53.5, which is a new one-year high. This provides a little more evidence that the private sector has weathered April’s shocks better than many had feared, even though hiring remains subdued.

This will not make much difference to the OBR’s long-term forecasts, but a more favourable economic backdrop for the Budget might limit any damage to confidence from another round of tax hikes.

Fifth, and finally for now, there will be more time for the UK economy to feel the benefits of less restrictive monetary policy. This includes the scaling back of bond sales (under the policy of “Quantitively Tightening”) which the Bank of England’s MPC is set to announce later this month, and the prospect of another rate cut in early November.

Admittedly, this is all rather Micawberish (“something will turn up”). Even in a best-case scenario the Budget is likely to include at least another £20 billion of tax rises, and there is little in the track record to date to suggest that this Government has any credible economic plans. But the long twelve-week run up to 26 November might still provide some opportunities to prove the doubters wrong – myself included.

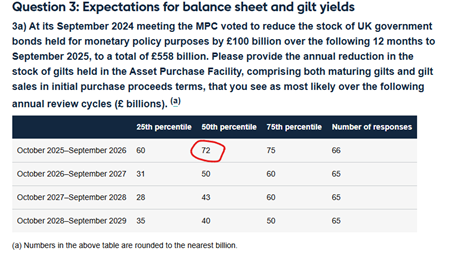

Ps. on quantitative tightening, the Bank itself has estimated that the QT programme has added 0.15-0.25 percentage points to 10-year gilt yields. Moreover, QT has dampened the growth of broad money and undermined the real economy.

Market participants surveyed by the Bank already expect the pace of QT to be reduced from £100 billion to about £72 billion in the coming year, so the reduction will have to be larger than that to have a significant impact on confidence and yields.

In my view, there is a strong case for pausing QT completely pending a full review of the policy, including the appropriate interest rate to pay on the additional reserves created under QE. But failing that, I would reduce the pace of QT more aggressively than the markets currently expect – say to £50 billion in the coming year – while emphasising that any active sales will be focused on shorter-dated bonds.