It has felt like an eternity, but Chancellor Rachel Reeves will finally unveil her second Autumn Budget on Wednesday 26 November. This blog begins with an explanation of how the Budget process works, then attempts to estimate the size of the new financial hole. The next instalment will look at how she is likely to fill it.

A primer on the fiscal framework

A good place to start is the Government’s two main ‘fiscal rules’.

One is a ‘deficit rule’. This is a target for the current budget, which is the difference between day-to-day spending and revenues (mainly from tax) in any one year. This measure of the budget is required to be in surplus in 2029-30, based on the forecasts produced by the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

The other is a ‘debt rule’. This is a target for the stock of debt, defined as Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities (PSNFL), which has to be falling as a share of national income (GDP) by 2029-30.

These rules are far from perfect, but they have a certain economic logic. The ‘deficit rule’ is designed to ensure that the cost of current spending is borne by current taxpayers, rather than passed on to future generations. The Government can then only borrow to invest. The ‘debt rule’ should prevent the overall burden of debt, including borrowing for investment, from spiralling out of control.

So far, every Chancellor has aimed to meet these targets (or their earlier versions) with something to spare – known as the ‘fiscal headroom’. But this margin has recently been very slim. In particular, the current budget has been forecast to be in surplus by just £9.9 billion in 2029-30, which is a tiny amount in the context of overall taxation and spending (and only 0.3% of forecast GDP). On average, the fiscal headroom under previous Chancellors (back to 2010) has been much larger – at around £30 billion – even when levels of borrowing and debt were much lower.

The OBR currently assesses performance against these targets twice a year, usually alongside the Chancellor’s Spring Statement and the Autumn Budget. Each time, the OBR updates its Economic and Fiscal Outlook (EFO) to assess whether the fiscal rules are likely to be met. If the early forecast rounds identify any shortfalls, the Chancellor has time to take measures to fill the gaps, and these measures are then included in the final assessment.

For example, in the run up to the latest Spring Statement (March 2025), the OBR forecast that the current budget was on track for a deficit of around £4 billion in 2029-30. This was mainly due to a shortfall in tax receipts and to higher Government bond (gilt) yields and inflation, which raised debt interest costs.

The Chancellor then announced measures that the OBR judged would be sufficient to restore the current budget to a surplus of £9.9 billion. Importantly, these measures included a package of welfare reforms (mainly savings on Personal Independence Payments and health-related Universal Credit), which were estimated to reduce spending by £5 billion in 2029-30.

Put another way, the OBR identified a ‘financial hole’ of about £14 billion in the run up to the Spring Statement, assuming the Chancellor wanted to retain the existing headroom of just under £10 billion. This was then filled with planned spending cuts and some small tax increases.

Of course, this was dwarfed by the measures on both tax and spending announced in the October 2024 Budget. The economic and fiscal backdrop was largely unchanged since the previous forecast in March 2024 (the last under the previous Government).

But in her first Budget, the new Chancellor added around £70 billion to annual public spending over the next five years. Of this, about two-thirds was on day-to-day spending and the other third on public investment.

Just over half this increase in spending was funded by higher taxes, notably the increase in employer National Insurance (NI) contributions. In the final year of the forecast period, the October 2024 Budget increased the overall tax burden by about £40 billion. The rest came from even higher government borrowing.

While the Chancellor has never ruled out more tax rises if necessary to meet the fiscal rules, the hope was that the scale of the increases in her first Budget would be a “one-off”.

In remarks to the CBI on 24 November 2024, Rachel Reeves said “Public services now need to live within their means because I’m really clear, I’m not coming back with more borrowing or more taxes”.

Moreover, Labour ministers (at least until recently) have consistently underlined the commitments on tax in the Manifesto for the 2024 General Election. This stated that “Labour will not increase taxes on working people, which is why we will not increase National Insurance, the basic, higher, or additional rates of Income Tax, or VAT”.

Nonetheless, in recent weeks the Chancellor has paved the way for broad-based tax increases. In particular, she used a ‘Scene Setter’ speech on 4 November to argue that “if we are to build the future of Britain together, we will all have to contribute to that effort”.

How big is the new financial hole?

This prompts the question of what has gone wrong? This month’s Budget may not have to repeat the full £40 billion of tax increases announced in October 2024. But another package of tax increases of at least £20 billion is now widely expected – and it may well be much larger.

Table 1 is an educated guess at the size of the hole to be filled – £30 billion – and the key components. This is a summary of how changes in the economy and fiscal backdrop since the OBR’s previous forecast in March, as well as the impact of new policy measures – might affect borrowing and debt in 2029-30. All these numbers are only indicative and there are many different ways of arriving at the same total, or a much higher or lower figure.

1. Productivity downgrade – £20 billion cost

The first line shows the biggest single element – the fallout from a long-expected downgrade in the OBR’s forecasts for trend growth in productivity. Depending on the context, productivity can be measured as output per hour worked, or as GDP per head.

Crucially, the OBR’s forecasts for productivity have proved to be too optimistic for many years. In fact, the Chancellor might be forgiven for feeling aggrieved that the latest downgrade is happening on her watch.

Ministers have suggested various factors to explain the timing of the downgrade. One is the claim that the initial impact of Brexit has been more negative than the OBR had already assumed – though there is little evidence to support this.

They have also emphasised the legacy of ‘austerity’ in the early 2010s (which is debatable) and the disruption to world trade from US tariffs (which is now fading).

A much simpler explanation is just that the OBR has been wrong on trend productivity for a long time and has decided to bring its estimates down in line with those of other forecasters, such as the Bank of England.

But whatever the precise reason, a downgrade to the productivity forecasts would mean that the UK economy is no longer expected to grow as much as before over the longer term. In turn, this is likely to reduce tax revenues and make it harder to meet the deficit rule. And while the deficit rule is still likely to be the one that bites, a larger annual deficit and a lower future path for GDP will make it harder to meet the debt rule too.

Table 1 reflects this by assuming a £20 billion hit from this downgrade, though a smaller figure of around £14 billion is also plausible.

2. Cost of borrowing – £2 billion cost

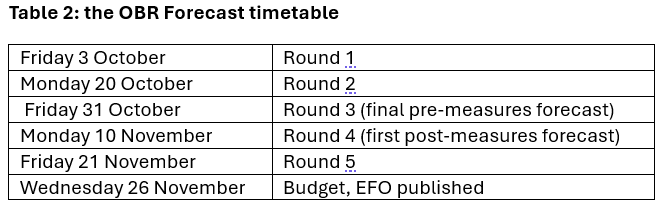

The second element in Table 1 is the change in the government’s cost of borrowing since March. The OBR’s assumptions here are based on average market expectations for Bank Rate (the official interest rate set by the Bank of England) and gilt yields during an ‘observation window’ ahead of the final pre-measures forecast. Table 2 sets out the timetable for this Budget.

The OBR decided right at the start of the process that it would take a later reading of market expectations for Bank Rate and gilt yields for the final pre-measures forecast, with this window covering the ten working days to 21 October.

As it happens, market expectations were a little lower in this period than in the previous ten working days (partly due to growing expectations of tax increases in the Budget). But more importantly, they were still a little higher than in the ‘observation window’ for the March forecasts. To reflect this, Table 1 assumes a £2 billion hit.

However, the OBR could still adjust these assumptions if the final budget package differs significantly from what the markets are expecting – in either direction. Indeed, in the October 2024 Budget the OBR made the judgement that the additional borrowing was unlikely to have been fully anticipated by market participants, so added a ¼ percentage point to the forecasts for the Bank rate and gilt yields. This is a yet another example of how, even at this late stage, nothing is guaranteed.

3. Other economic assumptions – £8 billion savings

This component has a great many moving parts and is even more uncertain. It has been widely reported that more favourable assumptions – perhaps about inflation, wage growth and associated tax revenues – could reduce the size of the financial hole by several billion pounds.

It is also possible that the OBR might give a little more credit for the supply-side measures and other policy changes since the March forecast, such as planning reforms or new trade agreements.

However, the OBR could also take a less favourable view of other policies, such as the Employment Rights Bill which is likely to reduce labour market flexibility, or the knock-on effects of further increases in the National Living Wage, especially on the employment prospects of younger people.

The OBR is unlikely to ignore the persistent weakness of housebuilding, which suggests that the planning reforms are set to disappoint. And the EU ‘reset’ is also far from a done deal, making it difficult for the OBR to incorporate any benefits (even if the UK does not have to pay a high price for them).

A net saving of £8 billion has been pencilled in here, but this could be way off in either direction.

4. Net increase in welfare spending – £8 billion

Moreover, the Government is likely to increase public spending even further relative to the March forecast. The earlier welfare package saving £5 billion has already been abandoned, and winter fuel payments for pensioners have been partially reintroduced. Other possible new commitments, such as the tapering of the two-child cap on working-age benefits, could add to the overshoot, perhaps taking it to £10 billion. This is likely to be only partially offset by some small savings elsewhere, such as from the Motability scheme.

For simplicity, Table 1 assumes that all the £8 billion that might be saved from more favourable economic assumptions is spent, rather than banked.

5. Measures to cut household bills – £3 billion cost

The Chancellor has also signalled that she wants to do something to reduce household bills directly.

One frontrunner is the removal of the 5% VAT from domestic energy bills. This tax break might be popular, but it would also be poorly targeted – some of the biggest winners would be richer households who use more energy. It would also do nothing to address the fundamental reasons why the cost of energy is so high in the UK.

Moreover, the loss in revenues would need to be offset elsewhere, most likely now from increases in direct taxes. So, while cutting VAT on domestic energy bills might reduce headline inflation (temporarily), real disposable incomes could be little changed.

These points would also apply to transferring some green levies and other policy costs from household bills to general taxation, though a scaling back of some green subsidies would be a net benefit to the taxpayer.

6. Increase fiscal headroom – £5 billion cost

Finally, the Chancellor has signalled that she wants to increase the fiscal headroom to provide a bigger buffer against future shocks. This is a good idea.

For a start, it should reduce the need for constant tinkering with tax and spending, sometimes within year, providing some stability. It may also give households and businesses a little more confidence that the Chancellor will not have to come back again with another round of tax increases any time soon.

Ideally the Chancellor would at least double the headroom – to about £20 billion. But larger tax increases now could also risk a bigger hit to the economy. Table 1 therefore assumes that she increases the headroom by a modest £5 billion, to about £15 billion. This would be better than nothing, but still only a small step in the right direction.

The upshot is that, based on some reasonable assumptions, the Chancellor could have to find another £30 billion from further tax increases.

Next up – how might she do this?

One thought on “The Chancellor is set to raise taxes again – by as much as £30 billion”