This weekend the Sunday Telegraph led with Britain ‘heading towards IMF bailout’, citing three leading economists who are warning of a “1970s-style debt crisis unless the Chancellor changes course”. The three – Jagjit Chadha, Andrew Sentance and Willem Buiter – are not the usual suspects and their views should be taken seriously.

The story was prompted by an interview that Professor Chadha gave to Liam Halligan, which is also worth a read.

As it happens, I still think speculation about another IMF rescue package is overblown. (On this I agree with David Smith, who has also written on this today.)

Crucially, the bailout in 1976 was a US dollar loan which was mainly used to pay back other countries. They had lent foreign currencies to the UK government as it attempted to prop up the pound. That is simply not the problem now, as we borrow in our own currency. The UK is not facing a sterling crisis, and the government would be right to let the pound fall if we were.

Any IMF bailout would also come with such punitive conditions that it would be politically unacceptable, including big cuts in public spending. (The IMF has raised concerns about other Labour policies too, such as the Employment Rights Bill, which may have to be scrapped.) Put another way, if the UK government were willing to take these tough decisions, we would not need the IMF in the first place.

Nonetheless, I would not rule anything out entirely. Professor Chadha has made the reasonable point that IMF involvement might enhance the credibility of the fiscal framework and restore some market confidence, thus attracting more private capital which could dwarf the limited resources available to the IMF.

Or as Doug McWilliams put it in a post on X, “if the UK goes to the IMF, it’s not because we need the currency (we didn’t really in 1976 either). It will be because the Chancellor needs an external stick to beat up those in her party who are resisting public spending cuts.”

I am not convinced that this would fly. An IMF-imposed austerity programme would surely be the end for both Rachel Reeves and Keir Starmer, especially with the emerging threat from Corbyn’s new far-left party. The markets would not necessarily be impressed, either.

Interestingly, recent events in France illustrate both sides of the argument. Finance Minister Eric Lombard warned on 26 August that an IMF bailout was “a risk that is in front of us”, partly to bolster support for the French government as it faces a confidence vote over a proposed austerity budget. But he then backpedalled as opposition politicians seized on the warning and as the markets reacted badly.

However, there is little doubt that the recent increases in the cost of UK government borrowing are consistent with an emerging fiscal crisis and that a course correction may soon be required.

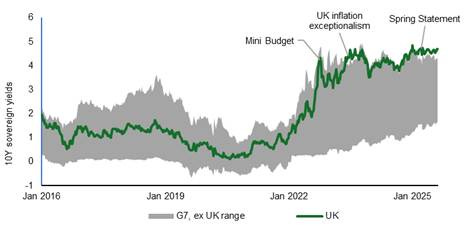

This chart – posted on X by Simon French – captures the problem clearly

As this chart shows, the UK now consistently has the highest government bond yields in the G7. Moreover, the “moron premium” (I don’t like that term but will use it anyway) which first appeared around the time of the 2022 mini-Budget now looks like a permanent feature.

To be clear, the rise in UK yields is part of a global sell-off due to concerns about inflation, government debt and bond issuance. There have been big moves in many other countries too, including Japan (where yields are at multi-decade highs) as well as France, and serious worries about the US.

But the UK is still an outlier, for three main reasons:

1. Investors are losing confidence in the UK government’s fiscal policies (especially after the failures to curb welfare spending) and are increasingly worried about a ‘doom loop’

2. the Bank of England has persisted with its policy of relatively aggressive bond sales (’active QT’), at a time when there are fewer domestic buyers (especially pension funds)

3. there are also fears that higher UK inflation will keep official interest rates higher for longer too, while adding to the cost of inflation index-linked borrowing (of which the UK has a relatively large amount)

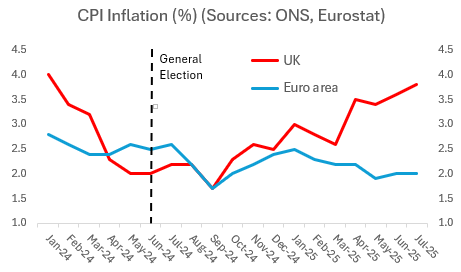

Indeed, after falling to the 2% target in the final two months of the last government, UK CPI inflation has now diverged sharply again from the euro area. This divergence mainly reflects increases in government-set prices (including domestic energy bills and the national minimum wage), the pass through of higher taxes (notably employers’ NI), and higher housing costs.

That said, there are some reasons for optimism:

September should be a better month for the bond markets – a US interest rate cut and any scaling back of QT by the Bank of England could lower the cost of UK government borrowing (though neither of these policy announcements would be surprises and may already be discounted).

The Autumn Budget is unlikely to be quite as awful as many now fear. In particular, talk of a £40-50bn ‘black hole’ is based on some pessimistic forecasts from NIESR, which is an outlier here. £20bn of tax hikes is more likely, and some of these will be backloaded towards the end of the forecast period (such as extending the freeze on personal income tax allowances) rather than taking effect straightaway.

In the meantime, the UK economy has weathered the twin shocks of Trump’s tariffs and Reeves’ first Budget a little better than expected – the labour market has cooled but not collapsed, and there are some encouraging signs on both consumer confidence (in the GfK and S&P Global surveys) and on business confidence (including the latest PMI, charted below).

Finally, inflation should now be close to its peak and there is more room for positive surprises (though I know Andrew Sentance would disagree with me here!). More evidence that underlying price pressures are fading would also make it easier for the Bank of England to cut interest rates again in early November

In short, the UK economy is not facing a re-run of the 1970s in every respect: GDP shrank by about 4% in total in 1974 and 1975, unemployment rose more sharply (from a low of 3.7% in 1974 to a peak of 11.8% ten years later), and both inflation (peaking at 22.6% in 1975) and interest rates were much higher (the Bank rate hit 15% in 1976).

Nonetheless, the public finances are now in a much bigger mess. The annual budget deficit was similar (averaging 6% of GDP in 1974 and 1975), but the stock of debt was far lower (about 48% of GDP, compared to 96% now).

There are policy similarities too, with public spending out of control and wage pressures strong (due to wage and price indexation in the 1970s and higher minimum wages now).

The upshot is that any temporary good news on the economy, or from the markets, may simply delay the inevitable reckoning. It might even be better if the crash came sooner rather than later. The underlying problems could then be addressed more quickly – with or without a shove from the IMF.