Brexiteers can be forgiven for indulging in a little ‘schadenfreude’ at the news that the EU has agreed the principles of a trade deal with the US on worse terms than the UK was able to achieve. Nonetheless, there are very few winners here.

For a start, a final agreement is still some way off. The US and the EU have simply agreed a framework for further negotiations. There is no legal text, and many important details have yet to be thrashed out.

It is therefore important not to take everything at face value. After all, key parts of the recent ‘deal’ between the US and Japan already appear to be unravelling. In particular, Tokyo is contesting Washington’s claim that the US will reap 90% of the benefits from joint investments.

The lukewarm response from many EU member states is also striking. The French Prime Minister, Francois Bayrou, declared “it is a sombre day when an alliance of free peoples, brought together to affirm their common values and to defend their common interests, resigns itself to submission.”

Other political leaders, notably German Chancellor Friedrich Merz and Irish Trade Minister Simon Harris, have welcomed the reduction in uncertainty and the prospect of lower tariffs for their key export industries. But this is hardly a ringing endorsement either.

Sweden’s Trade Minister, Benjamin Dousa, summed up the mood: “this agreement does not make anyone richer, but it may be the least bad alternative. What appears to be positive for Sweden, based on an initial assessment, is that the agreement creates some predictability.”

So, what do we sort of know? Frustratingly, there is no sign of an agreed text, but here is what can be gleaned from press reports.

1. The main headline is that a baseline US tariff of 15% will apply to almost all EU goods. Crucially, this will not be added to any existing tariff rates (at least that is what the European side is saying). This includes 15% on cars and car parts, compared to the current 27.5%.

2. For now, EU pharmaceuticals and semiconductors will remain tariff free, but this could rise to a maximum of 15% when the US completes a review of tariffs for these sectors worldwide.

3. Tariffs on European steel and aluminium will stay at 50%, again for now, but the EU and the US agreed that they will be replaced by a quota system to be negotiated later. In the meantime, there will be zero-for-zero tariffs on certain other goods, such as aircraft and generic drugs, with more to be negotiated too.

4. The EU has agreed to buy $750 billion worth of US energy during President Trump’s term in office, which is consistent with the existing plan to continue reducing Europe’s dependence on supply from Russia.

5. EU companies will invest $600 billion in the US, which is not obviously something that the EU itself can promise either, but probably not much different from the investment that would have taken place anyway.

At first sight, then, this looks worse than the deal that the UK has agreed.

For a start, the UK has a baseline tariff of ‘only’ 10%, rather than 15%. That said, the UK’s 10% is on top of existing tariffs, meaning in some cases the effective tariff will be higher than 15%. But the average should still be lower than the EU rates, and none of this has yet been finalised anyway.

The UK also already has a sizeable quota (100.000) for cars at the 10% rate, and is currently subject to a lower tariff of 25% on steel and aluminium.

The US-UK deal went further in other sectors too, notably opening up each other’s markets to more agricultural products, and lowering the cost of ethanol for UK consumers. Some protectionists have tried to spin the prospect of more US imports as a ‘loss’ for the UK, thereby showing they completely misunderstand the point of international trade!

The upshot is that this is another ‘Brexit win’. As the Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds put it, “I’m absolutely clear, this is a benefit of being out of the European Union, having our independent trade policy, absolutely no doubt about that.”

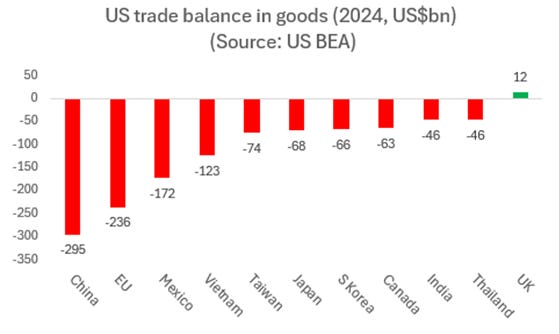

Admittedly, this simply follows automatically from the fact that the US runs a trade surplus on goods with the UK (at least on the basis of the US data), rather than a huge deficit, as it does with the EU. 10% is the default ‘reciprocal tariff’ for any country in the UK’s position. But if the UK were still in the EU, this would not apply.

What’s more, the EU’s much vaunted ‘greater bargaining power’ has counted for precisely nothing. In fact, as the leading French economist Olivier Blanchard has acknowledged, “the larger the group that must collectively take a tough decision, the less likely the decision will be taken. Europe is composed of 27 very different countries. It is its strength, but it is also its weakness”.

I would add that this applies to more than just trade, where the EU is notoriously slow to do deals, but also to other areas such as regulation, where the EU’s one-size-fits-all approach is rarely optimal.

But amidst all the point scoring, let us not forget that US tariffs are still much higher now than a year ago, including on the UK and others, as well as on the EU. World trade will therefore still suffer as a result.

And remember too that almost all the cost of higher tariffs (perhaps 90%) will eventually be passed on to US companies and households, so President Trump has not created many winners at home either.

In short, the worst-case scenario of a global trade war may have been avoided. But the outcome is still bad for all sides.

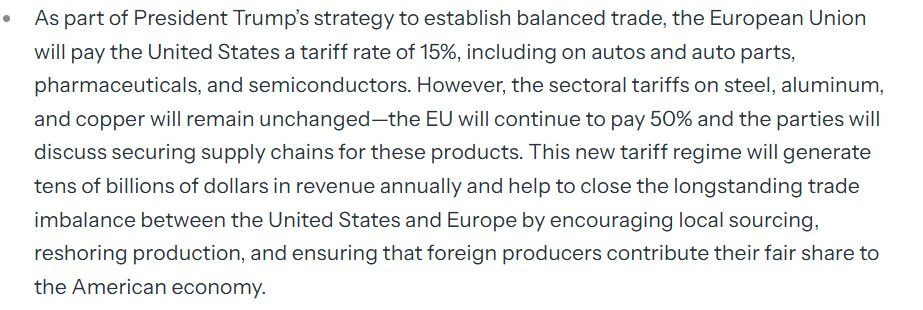

ps. (added 29 July) we do now have the White House version of the deal, here. My two takeaways are that 1. it is economically illiterate, and 2. it reveals big gaps between what the EU thinks they have signed up to and what the US expects.

The paragraph below illustrates both points…

This is bad economics because it is not the EU that pays the tariffs; they are collected from US importers and most of the burden (perhaps 90%) will fall on US companies and households.

Moreover, the EU still seems hopeful that they can negotiate lower sectoral tariffs on steel and other metals and further reductions in the tariffs on other key exports, notably pharmaceuticals. But there is no acknowledgement of that from the US side!