Steve Reed, the newish Secretary of State for Housing, has certainly brought fresh energy to the role. This has even extended to waving MAGA-style caps with Trump-like calls to “build, baby, build!”. But while it is still early days, little has improved on the ground.

The construction sector is worth watching closely for at least three reasons.

First, construction activity is a significant chunk of the UK economy, accounting for about 6 per cent of GDP. This share has remained relatively stable over decades even as the contributions from other “traditional” industries have declined, notably those from manufacturing and agriculture.

The sector also directly employs just over two million people. However, this figure is the lowest since the late 1990s, and workforce shortages are a critical constraint.

Second, the output of the construction sector provides many other social and economic benefits, including the supply of vital services and potential improvements in productivity.

New housebuilding represents around a quarter of the total, with another fifth coming from the repair and maintenance of existing homes. The rest is split between infrastructure spending and other public investment, and private industrial and commercial projects.

Third, the performance of the sector has become a bellwether of the success (or otherwise) of the new government’s missions in several areas.

Most obviously, Labour’s 2024 manifesto promised to “get Britain building again” with 1.5 million new homes in England over the course of a five-year parliament. This amounts to an average of around 300,000 a year (or more realistically, 200,000 in the early years, ramping up to 400,000 in the later ones).

In addition, the government has promised to increase public investment substantially compared to previous plans. And the willingness of private companies to commit to new factories, offices and other commercial spaces is an acid test of confidence in the wider economy.

Unfortunately, then, the latest omens are not good. The S&P Global UK Construction Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which tracks changes in total industry activity, was just 40.1 in December 2025. This was a marginal improvement on the 39.4 in November but remained below the neutral 50.0 level for the twelfth successive month, and still the second-lowest reading since the pandemic in 2020.

Worryingly too, the recent weakness in the PMI survey has been broadly spread across housing activity, civil engineering, and commercial construction.

This weakness has not yet been reflected in the official data. However, the latest hard numbers on housing starts and completions remain well below the levels needed to meet the government’s 1.5 million target.

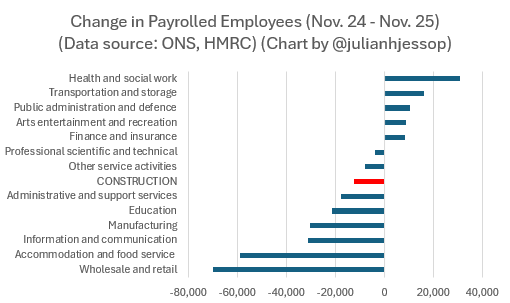

The construction sector has also continued to shed jobs, suffering (like most others) from the increases in labour costs imposed by Rachel Reeves’ Budgets.

So, what has gone wrong?

The weakness in UK construction partly reflects headwinds which are also seen in other countries, including heightened geopolitical uncertainty, higher global input costs and past increases in interest rates. Indeed, the construction PMI for the euro area has been below the neutral 50.0 level for even longer (44 months).

Activity might therefore pick up of its own accord as these headwinds fade and especially if UK interest rates continue to fall. Conditions are already looking a little brighter in the rest of Europe, where borrowing costs have dropped further and more quickly. The additional drag from pre-Budget uncertainty in the UK may simply have delayed the recovery in construction here by a few months.

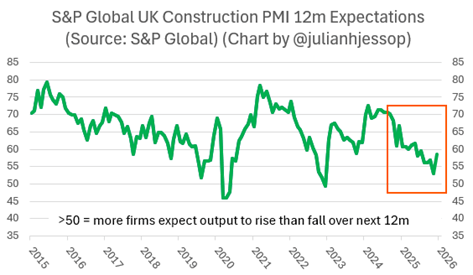

Consistent with this, the latest PMI survey found that firms have become more optimistic about the outlook for the year ahead – albeit only marginally (as the chart below shows). Some respondents expressed hopes that this year would see an increase in new work in the utilities sector, notably water and energy infrastructure.

Nonetheless, expectations are still weak by past standards, both in the PMI survey and in other polls. 2026 is generally predicted to be better for the construction sector than 2025, but industry forecasts for growth this year are typically being revised down.

This is doubly disappointing, because the Labour government has announced some initiatives which have been widely welcomed. These include a new National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) which, among other things, should make it easier to build housing around railway stations in the “green belt”.

The passage of the Planning and Infrastructure Bill should also reduce delays in housebuilding and speed the construction of new infrastructure, including reservoirs and electricity connections.

But Labour’s “build, baby, build” mission is still struggling to launch.

Despite the best intentions of some in central government, there are plenty of obstacles at the local level, as well as disproportionate costs imposed by bodies such as the new Building Safety Regulator. Rules on everything from biodiversity to parking spaces are still making developments less attractive.

Private developers are also being deterred by obligations to include “affordable” housing. These rules essentially require developers to provide some properties at below market rates, making any project less profitable and reducing the supply of new homes of all kinds.

Meanwhile, even ugly multistorey car parks being protected from redevelopment by new “heritage rules”.

The government’s attempts to ramp up public investment have also been patchy. Increases in spending on water and sewerage infrastructure and on defence facilities seem to be the only safe bets. Investments in energy generation and supply are at the whim of Ed Miliband’s “net zero” agenda, while investment in road and rail infrastructure looks set to fall short.

More generally, confidence is low – among households, businesses and investors, not just in the construction sector. Political and economic uncertainty is increasing again, property taxes are being raised, and Labour’s constant U-turns on other policies are not helping. The government appears too weak to stand up to any pressure group, including the “NIMBYs”.

In the industrial and commercial sectors, new demand seems overly dependent on investment in data centres. As for housing, it is hard to enough to sell existing homes, let alone have the confidence to build new ones.

Here the construction industry may have rely more on repair and maintenance, including energy-efficiency and fire safety work. Much of this activity is heavily dependent on government subsidies and, in any event, will not help Labour hit the 1.5 million-home target.

Overall, housing and infrastructure are two areas where the government is doing at least some of the right things. But Labour’s mismanagement of the rest of the economy is crushing the “animal spirits” that drive growth – including in the construction sector.

This piece was first published in the Sunday Telegraph on 11 January 2026

You can also follow me on X (formerly Twitter) @julianhjessop and on BlueSky

I also now post regularly on Substack