The answer to this question partly depends on your definition of ‘recession’, but I can think of at least three ways of approaching it.

First, “two quarters of falling GDP”? Probably ‘no‘, or at least not yet.

Second, “two quarters of falling GDP per head”? Almost certainly ‘yes‘. Indeed, we already appear to be in one.

Third, “a significant decline in activity spread across the economy and lasting more than a few months”? I could argue this one either way!

Let’s look further at each in turn.

The most popular definition of ‘recession’, at least outside the US, is two successive quarters where the economy contracts, as measured by total GDP. This is sometimes known as a ‘technical recession’. It is not an ‘official’ definition, but it is widely used.

In the case of the UK, GDP was flat in Q3 2024 so, unless that figure is revised downwards, we need to look at both Q4 2024 and Q1 2025 instead.

Based on the monthly figures already available for October and November, and on the plausible range for December, and again ignoring any possible revisions, GDP was probably either flat or down 0.1% in the final quarter of last year. We will not have the first official estimate until the December figures are released (on 13 February) but it’s not looking good. For now, I’ve pencilled in a fall of 0.1%.

What about Q1 2025? It’s too soon to be confident. The January indicators of household and business sentiment were almost all negative. These include the surveys of consumer confidence run by S&P Global and by GfK, and the CBI Growth Indicator which measures the expectation of private businesses for the next three months.

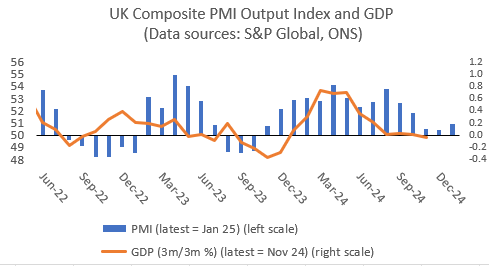

Nonetheless, the PMI index of private sector output in services and manufacturing edged up in January and was still above the 50 level that, in principle at least, marks the boundary between expansion and contraction.

There may also be a small boost from the public sector, which will not be captured by most polls. Other positives should include further reductions in interest rates (with the Bank of England now almost certain to cut in February) and a continued recovery in real household incomes (at least for those who are lucky enough to keep their jobs).

Admittedly, the main increases in tax and other business costs in Rachel Reeves’ first Budget will not kick in until April, and there will be a tough Spending Review in the meantime. But firms are already anticipating these changes so I suspect that a lot of the negatives are already in the data, while people on lower incomes are yet to benefit from the increases in the national minimum wage and state pension.

With some favourable base effects helping too, I’ve therefore pencilled in positive growth of 0.2% in Q1, meaning the UK should just skirt a ‘technical recession’ in terms of total GDP.

But I am much more confident that the UK is already back in recession in terms of GDP per head. This is not a particularly bold call: GDP per head shrank in every quarter of 2023, and it fell by 0.2% in Q3 2024. Continued population growth alongside flat or slightly negative total GDP means GDP per head almost certainly fell again in Q4 2024.

It’s touch and go whether growth in GDP per head will be negative again in Q1 2025, but I’m guessing not, so the UK may actually be about to emerge from recession on this definition. There is still no sign, though, of any meaningful growth.

Finally, like many other economists, I’m not that keen on the ‘two successive quarters’ definitions of recession. In part this is because a very large fall in activity in one quarter (say 5%) would not count as a recession on this definition if followed by even the slightest recovery (say 1%) in the next, even if growth over the two quarters is firmly negative (in this case, about 4%).

Moreover, focusing just on the single measure of GDP may miss some large underlying shifts in variables that matter much more for people and businesses.

For this reason, I prefer the NBER definition of recession commonly used in the US, which “involves a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months“. This includes indicators like real personal incomes, employment, retail sales volumes, and industrial production.

This definition is somewhat arbitrary, and I could probably argue it either way for the current situation in the UK. Employment, retail sales and industrial production are certainly all weak.

However, the NBER usually includes some measure of personal incomes as a key indicator. Here the UK should escape recession on this basis, because real household incomes and (especially) real wages are both still rising.

So, while the current downturn may feel like a recession to many, especially smaller businesses and those people losing their jobs, I do not think it would count as an economy-wide recession on the US definition. We cannot ignore the likely increases in public sector output either.

Does any of this matter, or is it just wordplay? In the bigger scheme of things, it is unimportant whether GDP rises by 0.1% or falls by 0.1%, especially given the almost inevitable revisions to come.

Nonetheless, headlines do matter for confidence in the economy, and can be self-fulfilling. The mere fact that we are speculating about ‘recession’ also shows how far the economy is falling short of the ambitions of the new government and the hopes of the rest of us.

As a benchmark, the October 2024 Budget assumed growth of 2% in 2025. I think we will be lucky to get half that number, and growth may even be slower this year than last. ‘Recession’ or ‘no recession’, there is little to cheer.

One thought on “Is the UK sliding back into ‘recession’?”