The Times is reporting today (Saturday) that the Chancellor is likely to confirm a rise in the National Living Wage (NLW) of about 4%, from £12.21 to at least £12.70, in next month’s Budget. She will also recommit to extending the full living wage to young people between the ages of 18 and 21 (where a lower rate of £10 currently applies).

This would not be a surprise.

The Government has already mandated the Low Pay Commission (LPC) to ensure that the NLW does not drop below two-thirds of UK median earnings. The LPC will make its final recommendations in the coming days, but the latest update (published in August) put this figure at £12.71 (a 4.1% increase).

Labour’s 2024 election Manifesto also committed to “remove the discriminatory age bands, so all adults are entitled to the same minimum wage, delivering a pay rise to hundreds of thousands of workers across the UK.”

This would continue a trend. Before April 2021 the full NLW was only for people aged 25 and over. It was then extended to those aged between 23 and 25, and again from April 2024 to those aged 21 and 22.

But going further would still be a bad idea – and the timing is terrible.

In my view, there is a reasonable case for a basic minimum wage to protect the most vulnerable workers from exploitation.

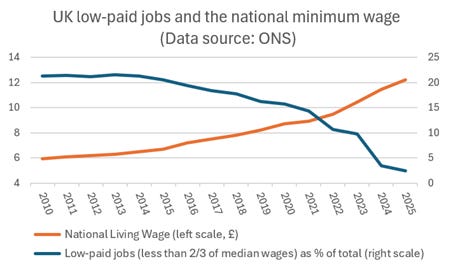

Viewed positively, the NLW has helped to lift many people out of low pay (defined as earning less than two-thirds of the median hourly rate). The latest ONS data show that the proportion of employees who are ‘low paid’ has fallen from 21.3% in 2010 to a series record low of just 2.5% in 2025 (mostly under the Tories).

What’s more, the sizeable increases in the NLW during the 2010s did not lead to the large-scale job losses that some had feared.

However, this was because the NLW was set at sensible levels, based on evidence and the (then) independent advice provided by the LPC, with lower rates for young people. In other words, the policy was successful in its early stages precisely because it was not too ambitious. This lesson is seemingly lost on today’s cheerleaders for further big increases.

The situation is very different now – for three main reasons.

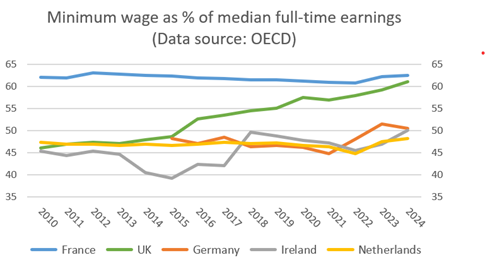

First, the level of the NLW is now much higher. OECD data show that the UK minimum wage is already one of the most generous (relative to average pay) among the major economies. and rapidly catching up with France. This should ring alarm bells given that the French unemployment rate is 7.5% – and as high as 18.1% for young people.

Indeed, the Office for Budget Responsibility has already warned (in October 2018) that “a rise in the NLW to two-thirds of median earnings would raise the unemployment rate by 0.4 percentage points in the ‘target’ year. In today’s terms that corresponds to a rise in unemployment of around 140,000, plus an equivalent reduction in hours for those remaining in employment. Average hours would be 0.4 per cent lower and real GDP 0.2 per cent lower than they otherwise would have been”.

Second, the latest increases in the NLW are coming at the same time as businesses are being saddled with many other additional costs, including the hike in employers NI and the extra red tape in the Employment Rights Bill.

It is no coincidence that the biggest job losses over the past year have been seen in sectors, like retail and hospitality, where the increases in labour costs have bitten hardest.

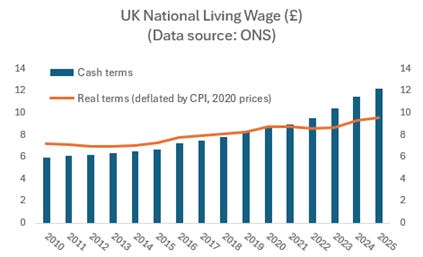

An additional 4% or so on the NLW may not sound like a lot, but it would be on top of a 40% increase (in cash terms) since 2020.

Third, extending the full rate to 18 and 20 year olds is an especially bad idea at a time when so many young people are already struggling to find work.

Remember the national minimum wage for 18 to 20 year olds is currently £10. If this is raised to the predicted level of the full NLW in 2026 – £12.71 – that would increase the cost of employing a young person by 27.1% (or more, taking account of other charges such as NI on top).

Of course, many employers will already be paying 18 to 20 year olds the same as older workers. But for those who are not, a 27.1% cost increase could be a game-changer.

The case for a lower rate for younger workers was summarised by the LPC back in 2020. In particular, “evidence shows that younger workers are at higher risk of being priced out of jobs than older workers. They are also more likely to experience a ‘scarring effect’ if they spend time out of work, with lower wages that can last several decades. Above all else, we want to ensure that the youth rates are set at a level that means young people are not excluded from the labour market.”

Unfortunately, that advice is now being ignored. Instead, a bigger increase in the NLW for young people looks set to penalise new starters in favour of older, more experienced staff who require less supervision. This will compound the disincentives to hire relatively unknown new starters which are being built into the Employment Rights Bill.

For those who might be thinking ‘why should young people be paid less for doing the same job’, remember that the NLW is a floor, not a cap. There is nothing to stop employers from paying young people more than the NLW – and the same as older staff – if their work is indeed of equal value.

Above all, those cheering on the increase in the NLW fundamentally misunderstand the economic realities.

The Government does not “give people a pay rise” by increasing the National Living Wage. Instead, the money comes from employers.

This may partly be reflected in lower profits, which is still bad for future investment and growth. But it is at least as likely that higher costs will be passed on as some combination of higher prices, cuts in non-wage benefits, lower wages for other workers, and fewer jobs. For employers in the public sector, higher labour costs will be reflected in higher taxes and lower service levels.

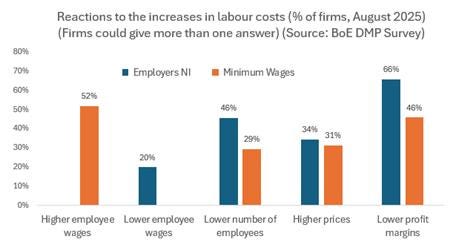

A recent Bank of England survey provided more evidence on how firms have already responded to the policy-driven increases in labour costs.

This survey showed that the recent increases in minimum wages have boosted pay, but this is partly offset by the negative impact on wages from the increases in employers NI. Both measures have cost jobs and raised prices, as well as squeezed profit margins.

The knock-on effects of higher minimum wages on the earnings of workers higher up the pay scale can go either way too. Some might see bigger pay increases than otherwise to maintain pay differentials. But others might find that their pay rises more slowly as employers look to find savings to offset a higher minimum wage, compressing the distribution of pay. There is certainly a marked concentration of jobs paid within 20 pence of the NLW.

Some firms might also invest more to increase productivity, but this is most likely to take the form of the automation of lower-paid jobs, again increasing unemployment particularly among younger people.

In summary, increasing the NLW even further is not a painless way to tackle the cost-of-living crisis. At the least, the Government should delay plans to extend the full minimum wage to younger workers. As it stands, this policy is one of many which are increasingly likely to harm the very people they are supposed to help.

PS, you can follow me on X (formerly Twitter) @julianhjessop and BlueSky @julianhjessop.bsky.social. I also post regularly on Substack at https://substack.com/@julianhjessop