Rishi Sunak is warning that a one percentage point increase in the interest rates paid on government debt could add £25bn to the annual debt interest bill. Does this stack up? And how worried should we be?

For a start, the £25bn figure is factually correct. There has been some confusion about this on Twitter, with Richard Murphy even accusing the government of a ‘straightforward lie’.

Murphy might have a better point if Sunak was only talking about ‘gilt yields’, or the ‘immediate impact’. But the £25bn refers to ‘all interest rates’ (front page of Saturday’s FT) and to the impact of ‘a one percentage point increase in the cost of borrowing’ on the annual bill ‘by the end of the parliament’ (front page of the Sunday Times).

What’s more, £25bn is clearly in the right ballpark. Very crudely, the OBR is forecasting that public net debt will top £2,500bn within a few years, and of course 1% of this would be about £25bn.

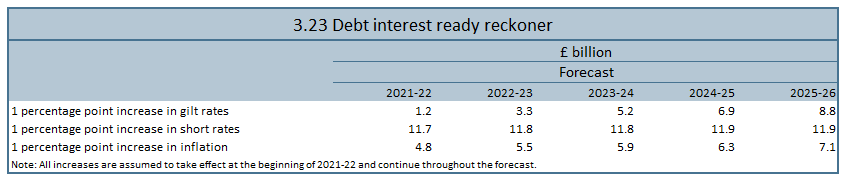

This figure is also justified in a more sophisticated way by the OBR’s ready reckoner (table 3.23 in the November 2020 Economic and Fiscal Outlook – supplementary fiscal tables: expenditure) which I’ve reproduced below. The numbers here take full account of the long maturity of borrowing in the gilt market, but also the fact that the Bank of England has reduced the effective maturity of government debt by swapping gilts for central bank reserves which pay the Bank’s short-term interest rate (currently just 0.1%).

Admittedly, to arrive at the £25bn figure in 2024-25 you have to assume that conventional gilt yields, the cost of borrowing via inflation index-linked gilts, and, most importantly, short-term official rates all rise by an additional one percentage point. But the Chancellor did say ‘(all) interest rates’, so this is not inconsistent.

Nonetheless, we can question the circumstances in which all these rates might rise. The £25bn figure is what it is and not wrong. But are the underlying assumptions credible?

Many MMTers (including Murphy) dismiss the possibility of any increase in short-term rates, presumably on the basis that the government could order the Bank of England to continue QE and funding asset purchases at just 0.1%, regardless of economic and financial conditions and whatever is happening to inflation. But it’s not obvious that this is any more plausible.

Even if it would be legal to trample over the Bank’s independence in this way, it would undermine credibility and market confidence. The result would probably be a run on sterling and an even bigger rise in gilt yields (including inflation index-linked gilts, of whose existence some people still appear blissfully unaware).

A more sensible argument is to that the impact of any increase in interest rates also depends (crucially) on why interest rates are rising.

It’s overwhelmingly likely to be because the economy has recovered more quickly than expected. This would then provide an offsetting boost to the public finances in the form of higher tax revenues and lower welfare spending (aka the ‘automatic stabilisers’).

To illustrate this, as a rough rule of thumb, a 1% increase in GDP reduces borrowing by 0.5% of GDP. The OBR is also forecasting that GDP will be over £2,500bn in 2024-25, so even if GDP is just 2% higher than expected by then (not unreasonable), underlying borrowing will be £25bn lower. This would offset the cost of a 1pp increase in interest rates on the debt, at least in that year.

Just as importantly, it would reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio too. This matters far more than the absolute size of the debt (in terms of billions, or even trillions, of pounds). (I recently wrote some more on the debt-GDP-ratio here.)

Put another way, rather than having to raise taxes or cut spending by £25bn, the government could borrow an additional £25bn to pay the interest, add this to the stock of debt, and the burden of debt (represented by the debt-to-GDP ratio) would still fall as the economy grows.

Rather than worrying about the risk that interest rates might go up, it makes more sense to think about where interest rates (r) are relative to the growth rate of the economy (g) – and to worry about g. As long as r < g, there’s plenty of fiscal space.

In short, the Chancellor should continue to focus on boosting economic growth in the Budget, rather than ‘consolidating the public finances’. (On that at least, I’m sure Richard Murphy and I would agree.) And this is despite the recent jump in gilt yields, which are still extremely low.

Richard Murphy is of course correct in his assertion that ‘the market’ doesn’t decide what interest rate the government pays on its liabilities – the MPC does. So if the MPC thought it would be good policy to have the government pay an extra £25bn to those that held the govt’s liabilities as their financial assets, it could make that happen by putting rates up by 1%. If it believed it would be good policy for the govt to pay £50bn to those of us in the private sector that already have money, then it could, by putting up rates by 2% ……..etc etc etc.

Personally, I can’t see many circumstances whereby the government paying more money to those that have money would be considered ‘good policy’ (apart from by those that have money and would thus be in receipt of more money just because they have money, but, hey). For a start, just paying more money to the private sector is expansionary and could well be inflationary. Doing something that would be inflationary in order to combat inflation…..well, they surely must have some better ideas!. But if it was believed to be ‘good policy’ for the govt to pay more to the private sector (for whatever reason), there are surely better ways of the government spending that money.

Surely it would be better for the govt to fix the rate it pays on all its liabilities, at zero maybe, or its inflation target of 2%, or any other level that made sense and then supply as many liabilities as the non-govt sector (including the foreign sector) wants to hold. My guess is that if it set the rate at more or less zero, the quantity that would be demanded would be, oh, I dunno, maybe somewhere around £2.2trn to £2.5trn…which would be handy, because that’s roughly the amount currently being demanded with interest being paid on those liabilities of roughly zero (the foreign sector aren’t rebelling and causing a ‘run on the pound’ so unlikely they would if the current situation was formalised!). If the amount is more, supply more by continuing to run deficits. If its less, run a surplus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for an informative blog.

Grateful if you would clarify:

‘a 1% increase in GDP reduces borrowing by 0.5% of GDP. The OBR is also forecasting that GDP will be over £2,500bn in 2024-25, so even if GDP is just 2% higher than expected by then (not unreasonable), underlying borrowing will be £25bn lower. This would offset the cost of a 1pp increase in interest rates on the debt’.

By ‘offset’ I presume you mean ‘diminish’ rather than ‘balance’ the cost of an increase in rates: the reduction in the stock of borrowing would have to be much greater than £25bn to balance the £25bn additional flow cost of a 1pp increase in interest rates on the debt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks John. You raise a good point. It wouldn’t be enough for GDP to be 2% higher than otherwise in just one year, unless the 1% increase in interest rates also lasts just one year. In other words, the path of GDP would need be 2% higher for as long as interest rates are 1% higher. But given that some people think that Covid might cause long-term damage to the economy so that GDP is effectively permanently lower than otherwise, I think its fair to talk about an ‘upside scenario’ (as the OBR did last November) where there is no such scarring. That’s also the scenario when interest rates might be higher.

LikeLiked by 1 person