Another month, another set of scary numbers on the public finances: the UK government borrowed an additional £36 billion in September and total public debt rose to £2,060 billion, or around 103.5% of national income (GDP). But there is still no need to panic.

For a start, the figures are entirely as expected. If anything, they are not as bad as feared. Government borrowing continues to undershoot the latest official estimates published in August by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

Indeed, actual borrowing in April to September was £54 billion lower than the OBR had projected. That’s a useful figure for anyone making the case against tax rises to fill a potential ‘black hole’ in the public finances left by Covid, or for those arguing for just a few million extra for cities facing local lockdowns.

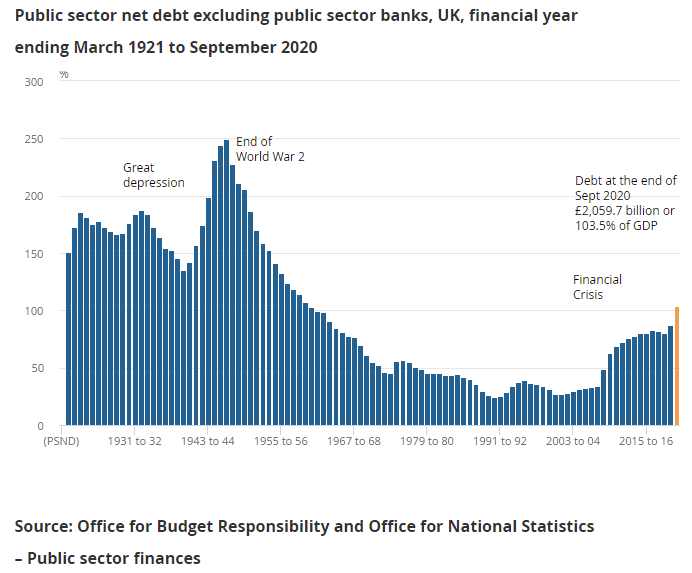

The debt numbers are not quite as awful as they look either. There was a lot of understandable concern when total public debt exceeded the landmarks of £2 trillion and 100% of GDP. (Actually, subsequent revisions to the data have allowed the media to run these headlines more than once!)

Nonetheless, the £2 trillion includes a contribution of £226 billion related to additional asset purchases and lending by the Bank of England. These are assumed (rather oddly) to add to net debt until they are redeemed or repaid, which is purely an accounting technicality. Excluding these temporary impacts, public sector net debt is still ‘only’ £1,834 billion (or 92% of GDP).

More importantly, debt has been much higher than this in the past. The OBR’s public finances database shows that debt peaked at just under 250% of GDP in 1946-47 in the wake of WWII, then fell sharply as public spending and economic activity returned to more normal levels.

In the meantime, the government is having no problem financing this increased debt by selling bonds (‘gilts’) to private investors, in the usual way. In practice, most of these bonds are then being bought by the Bank of England in the secondary market using newly created money as part of ‘Quantitative Easing’ (QE). But the fact remains that private investors are willing to pay very high prices for these bonds, and the Bank of England has to pay equally high prices to take them off their hands.

As a result, the effective interest rates on this borrowing are very low. It now costs the UK government just 0.2% a year to borrow for ten years. Borrowing costs over shorter periods (up to five years) are actually negative: investors still receive regular interest, but when the bonds mature they get back less than they paid for them.

Even if interest rates do rise soon (which would be no bad thing), the average maturity of UK government debt is a good 15 years. This leaves plenty of breathing space. Put another way, there is no need to worry about paying back the money anytime soon – and the debt can always be rolled over anyway.

Just about the only market participants worried about all this are the rating agencies. Last week, Moody’s downgraded the UK’s sovereign rating from ‘Aa2’ to ‘Aa3’. But the UK is unlikely to be alone here. At the last count, rival agency S&P had 31 countries on ‘negative outlook’ (as shown in the Reuters chart below).

UK debt is also still lower as a share of GDP than many other major economies, including Japan (where it has been well above 100% of GDP for as long as I can remember).

Above all, it is always worth asking – what is the alternative? In other words, what would happened if the UK government had not been willing to increase spending and borrowing in response to an unprecedented economic shock, when GDP collapsed by 25% in just two months? Indeed, when it affirmed Australia’s triple-A rating this week, S&P said a large economic stimulus will support the country’s recovery.

Obviously, this scale of fiscal support cannot continue indefinitely – but then it shouldn’t have to. As and when the economy recovers, the emergency schemes can be withdrawn, tax revenues will recover, and the welfare bill fall again.

Even if the level of public debt remains higher, the burden will fall sharply as a share of GDP as GDP itself rebounds. The temporary impact of the activities of the Bank of England will also drop out of the numbers in a few years.

Finally, it is worth stressing that the onus of responding to this crisis should fall on fiscal policy. There is already speculation that the Bank of England will announce some additional QE at its meeting in November. In my view, this would be a mistake: consumer price inflation (excluding the temporary effect of tax changes) is 2.2%, inflation expectations are at a multi-year high, and the money supply is booming. Monetary policy sometimes needs to support fiscal policy, but the Bank of England’s main job is to manage inflation, and there is already more than enough monetary stimulus to keep borrowing costs down.

The upshot is that the Treasury should not be afraid to spend and borrow a little more, if required. There may be other and better reasons to worry about increased state intervention, but the cost of paying for all this should be well down the list.

PS. since I first wrote this piece the Chancellor has announced some additional financial support for businesses and jobs. This doesn’t change the story here. If anything, the extra government spending is another reason why the UK doesn’t need even more monetary stimulus…

It is debatable whether the additional Covid restrictions are appropriate, but there is at least a good economic case for more financial support when businesses are unable to trade as normal.

It makes sense to protect jobs and incomes during temporary lockdowns, rather than expose firms and employees to the additional costs and uncertainty of firing and then rehiring again. This will also minimise the risk of longer-term economic scarring, including much higher unemployment.

This is the fair thing to do as well when particular regions, or sectors, are bearing a disproportionate share of the burden of a national crisis. Managing a pandemic is a textbook example of a ‘public good’ when a collective response is required.

In short, the additional hit to the public finances is a worry, but it is still right that fiscal policy plays its full part in preventing even bigger economic and social problems.

One thought on “How much should we worry about UK government debt?”