The real ‘news’ in today’s official GDP data for Q2 is not that the UK economy shrank for a second successive quarter in the three months to June, thus meeting the usual definition of a ‘recession’. That was a racing certainty anyway given the collapse in economic activity in April and the limited recovery in May, which had already been reported.

Given this, it was also no surprise that the UK is likely to have recorded the biggest quarterly decline in GDP of any major economy (but I’ll come back to the significance of this later).

Indeed, as well as being ‘old’ news, this is not necessarily even ‘bad’ news. The slump was the result of the government’s decision to shut down large parts of the economy and to discourage many people from doing what they would normally be doing – in order to save lives. It certainly seems odd for people who have been calling for even tighter restrictions to express dismay at the impact on GDP. Frankly, this is what they wanted.

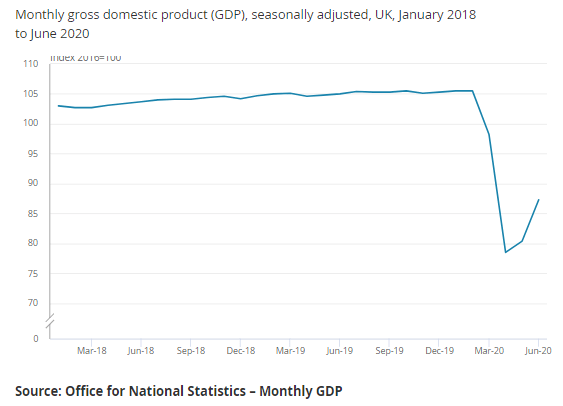

The real news today – the piece of the jigsaw that was still missing – is the monthly data for June itself. These confirmed that the recovery that began in May accelerated in June, with GDP rising by 8.7% in the final month of the quarter. (Dare I say that the shape below looks like the start of a ‘V’?)

It is also worth noting the small upward revisions to GDP growth in April and May (every little helps…). April’s fall was revised to a decline of 20.0% m/m (previously -20.3%), while May’s rise was nudged up to 2.4% m/m (from +1.8%). Taking these revisions into account, GDP is now up more than 11% from its trough in April. Even the 20.4% fall in the second quarter as a whole was not quite as bad as some had feared.

Of course, there is still plenty for the pessimists. For a start, GDP is still more than 17% below its level in January, before the pandemic struck. But these data only take us to the end of June, when the recovery was in its earliest stages. The latest business surveys and other timelier indicators suggest that the economy has continued to pick up since then.

Others have focused on the likelihood that the UK will be at the bottom of the league for growth in the second quarter. But there are excuses . In part this is because a relatively large share of the UK economy is made up of the types of consumer spending and services that are most likely to be constrained by social distancing. (This was a point underlined by the OECD in its June Economic Outlook, from which I’ve snipped the image below.)

However, the UK’s relatively poor showing in the second quarter is mainly due to two other factors. First, other countries began their official lockdowns earlier and so took a bigger hit to growth in the first quarter instead. If you combine the data for these two quarters, the fall in UK GDP was much closer to that in France or Italy, and actually slightly smaller than that in Spain.

Second, the UK GDP data more accurately reflect the falls in the output of the health and education sectors (a point explained well here by Mike Haynes). Most countries in Europe base their estimates for these sectors on the fact that staff costs and other bills were still being paid. But UK statisticians attempt to measure how much work was actually done.

(Incidentally, this also explains why the UK price ‘deflator‘ for the second quarter increased by as much as 6.2% q/q and 7.9% y/y. This wasn’t ‘inflation’ in the usual sense of rising prices, but a reflection of the fact that the volume of goods and services bought by the government in particular fell sharply while expenditure still rose in nominal terms.)

Admittedly, that’s not much to cheer. But the flipside is that the UK should leap towards the top of the table in the third quarter and beyond – assuming that the restrictions continue to be lifted and consumers and businesses continue to regain the confidence to spend.

As the chart below shows, there is still plenty of catching up to do in sectors such as hospitality, arts – and education. The next major milestone will hopefully be the return of children to schools in England in September.

Inevitably there are risks. It may be right to be worried about a fresh wave of redundancies in the autumn as the government’s Job Retention Scheme is wound down. But most people have already returned from furlough and our relatively flexible economy is good at creating new jobs to replace any that are lost – provided markets are allowed to work properly.

The additional measures announced by the Chancellor in his ‘Summer Economic Update’ should also be helpful, especially for the low-paid workers and younger people whose jobs are among those most at risk.

The other big unknown is the threat of a devastating second wave of coronavirus itself. But it should be possible to deal with any local outbreaks with local restrictions, rather than another nationwide lockdown.

In summary, April was dreadful, but the real message from today’s GDP data is that the economy is already rebounding. The recovery should therefore still look as much like a ‘V’ as the gradual lifting of the emergency measures allows, despite the prospect of a painful bump in unemployment in the meantime.

PS. A quick afterword on the accompanying data on productivity. Output per worker predictably slumped in Q2 (by 19.9%), mainly because people on furlough still counted as employed even if they weren’t actually working. But output per hour worked also fell, by 2.5%. Why…?

The key point here is that productivity is cyclical and usually falls even during ‘normal’ recessions, for three main reasons.

First, firms are less efficient at lower levels of output and capacity utilisation (loss of economies of scale, etc), even if workers put in the same hours.

Second, even without government subsidies, firms often ‘hoard labour’ during downturns until they are certain that workers are no longer required. This is because hiring and then rehiring them can be expensive. The upshot is that some workers will be kept on even if they have less to do, which also depresses productivity.

Third, recessions cause disruption. This may be good in the long run (‘creative destruction’), but the need for firms to find and work with new suppliers and customers can hamper productivity in the short term. The need to comply with social distancing rules isn’t helping either.

It is therefore no surprise that a record fall in GDP is accompanied by a record fall in output per hour. As the economy recovers, so should productivity. But the persistent weakness since the global financial crisis (the ‘productivity puzzle’) makes this one to watch closely.