Many people will read whatever they like into today’s new data on the labour market without bothering to look past the headlines. And to be fair, those raising concerns about the recent trends in unemployment and in pay are right to do so.

Nonetheless, the underlying picture is a little more nuanced. Here are four key points which many are still missing.

The first is what is driving the increase in the unemployment rate. The headline measure rose again to 5.2% in the three months to December 2025, hitting another post-pandemic high. Moreover, this measure is set to climb further in 2026 (it was 5.4% in December alone).

For what it is worth, I expect unemployment to peak at around 5.5% later this year, and to average more than 5% for several years.

However, employment is also still rising, at least according to the Labour Force Survey (LFS) on which these figures are based. Comparing the three months to December 2025 with the same period a year earlier, the number of people in employment (up 381,000) actually increased by more than the number who are unemployed (up 331,000).

The problem is that job creation is not keeping up with increases in the working age population and in participation rates (more people who were previously inactive in the labour market are now looking for work, which can be a “good thing”).

In turn, this explains why it is possible for both employment and unemployment to be rising at the same time. Put another way, this is mainly about a lack of hiring, rather than an increase in firing.

This also helps to explain why consumer confidence appears to be surprisingly resilient. Indeed, the latest S&P Global UK Consumer Sentiment Index found another small improvement in “job security”. If you already have a job, you might still be feeling fairly comfortable.

That said, the increase in the unemployment rate is still unwelcome, especially as younger people and other new entrants to the labour market are finding it particularly hard to find work.

Lots of factors have contributed here. But the single most important is a raft of government policies which have raised the cost of labour – notably the large increases in minimum wages and in employer NI contributions – and which are set to undermine the flexibility of the market even further – led by the Employment Rights Act (ERA)

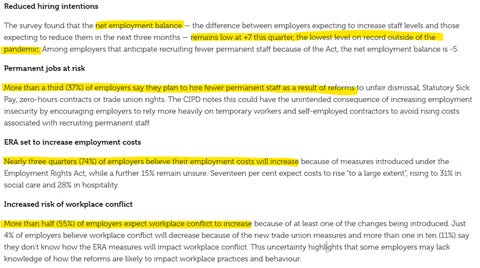

This was illustrated this week by the CIPD’s latest Labour Market Outlook, which provided a damning verdict on the (presumably unintended but entirely predictable) consequences of the ERA. I have pasted the key points below.

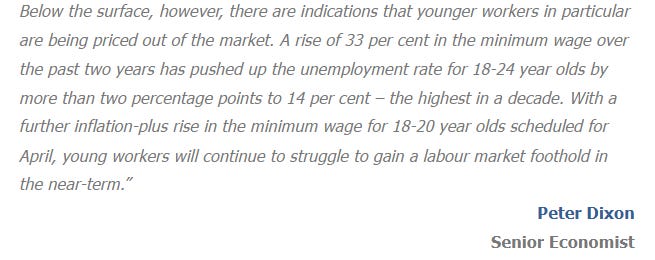

There is now a broad consensus that the increases in the national minimum wage have gone too far too and are damaging the job prospects of young people.

Here is a snip from the commentary on today’s figures from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

This echoes concerns raised last year by the Resolution Foundation (again, from the Left). As is so often the case, government intervention is harming some of the very people it is supposed to be helping.

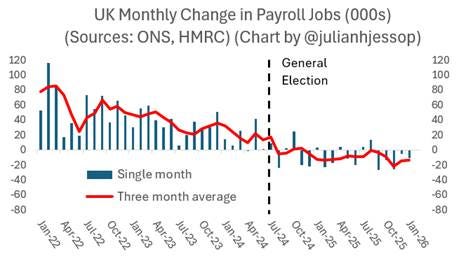

Slightly more positively, the second point many have missed is that the latest HMRC PAYE data (charted below) add to evidence that the weakness in hiring may be starting to level out.

The preliminary estimates suggest a net loss of another 11,000 payroll jobs in January, but December’s initial decrease of 43,000 was revised to a fall of “just” 6,000. It would not surprise me if January’s fall were subsequently revised to a small increase.

Again, and to be clear, this would still be bad news. Given the growth in the working age population and in participation rates, payrolls should be rising much more strongly.

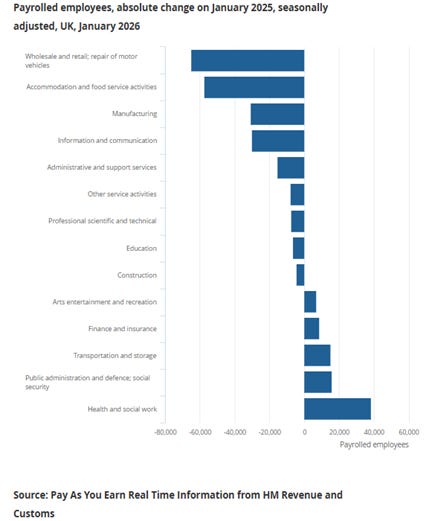

The sector breakdown also still shows the biggest job losses are in industries – notably retail and hospitality – where employment has been hit hardest by government policy choices. Equally, it is notable that the sectors posting the biggest increases are public administration and health and social work (predominately in the public sector too).

The third point is more nerdy, but also important. The divergence between the LFS and the HRMC PAYE figures (mainly on employment) provide a superb example of how hard it is to call the economy right now, especially what’s happening to productivity, given the conflicting signals from different data sources.

Specifically, based on the LFS, output per hour worked was 0.5% lower in Q4 2025 than in the same period a year earlier. But based on administrative data (notably the HMRC PAYE figures), output per hour was 1.6% higher!

Hopefully the latter are more accurate, in which case there is more scope for the economy to grow quickly without generating more inflation – good news both for the public finances and for those hoping for further cuts in interest rates.

But it would also be ironic if productivity has finally turned the corner so soon after the OBR has downgraded its forecasts…

My final point is about the divergence between the recent trends in public and private sector pay.

Many people are rightly concerned about the large gap that has opened up between the annual growth rates in regular pay in the private sector (3.4% in the three months to December) and in the public sector (7.2%).

But this partly reflects the timing of some public sector pay rises, which were paid earlier last year than in 2024. Crucially, this “base effect” is already fading. The single month growth rate of public sector regular pay has slowed from a peak of 8.5% in October to 5.6% in December.

The upshot is that the headline three month growth rate of public sector will start to drop more sharply from January. This is just maths.

Looking forward, I expect average pay settlements in the public and private sectors to converge at around 3-4% this year. This would be broadly consistent with price inflation returning to the MPC’s 2% target, if labour productivity is indeed picking up and if it continues to do so. But those still appear to be big ‘ifs’, especially in the public sector.

In summary, while the labour market remains weak – and this is largely due to government policy choices – it is perhaps not quite as weak as some headlines suggest. The divergence in trends in public and private sector pay – if not in productivity – should also be temporary.

ps. you can also find me on X (formerly Twitter) @julianhjessop and on BlueSky.

I also now post regularly on Substack