The BBC is reporting today that the Prime Minister is considering a significant increase in defence spending or, more precisely, that Keir Starmer is looking at bringing forward increases that have already been promised.

The Labour government has previously committed to raising core defence spending from a little under 2.5% of national income currently to the new NATO target of 3.5% by 2035, with an ambition to hit 3% of GDP in the next parliament. Apparently, the aim now is to meet that 3% ambition by the end of the current parliament, so no later than 2029.

To be clear, I am no expert on defence or security issues. (I recommend Tom Tugendhat @tomtugendhat instead, and following the commentaries published by RUSI). But here is an economist’s attempt to answer seven key questions.

1. Is it really necessary to increase defence spending?

There is a broad consensus on the need to ramp up spending on defence. The increasing threats posed by Russia, China and Iran were already eroding the post-war “peace dividend”. The creeping isolationism of President Trump’s America has made the risks even greater.

For the first time in generations, Europe is having to contemplate the cost of disconnecting its defence and security from the United States. For Britain, this could also include the additional cost of a truly independent nuclear deterrent.

Meanwhile, officials at the Ministry of Defence (MoD) believe they will require an extra £28 billion over the next four years just to cover cost increases. Of course, there may be an element of “talking their own book” here. But as Tugendhat has noted, Britain currently has enough ammunition to fight for just eight days.

2. Would 3.5% of GDP be enough?

The NATO target of 3.5% would still be well below the Cold War peaks, when UK defence spending topped 7% of GDP. Hopefully, though, there two good reasons why 3.5% might now be sufficient.

First, other (more reliable) partners are stepping up too. The pooled resources of Western European allies should be more than a match for Russia at least. Putin’s attempt to take over all of Ukraine shows his expansionist ambitions. But his failure to do so has also exposed the weaknesses of Russia’s armed forces.

In the meantime, the US still seems willing to stand up to China in the Asia-Pacific region, and to Iran in the Middle East.

Secondly, how money is spent is just as important as how much is spent. It is important to keep asking whether increased spending (inputs) actually enhances defence capabilities (outputs), and if it truly makes us safer (the ultimate goal).

Here, costs can be managed by more efficient procurement, which is something the UK has been terrible at in the past. What’s more, modern warfare is no longer about large and expensive standing armies. It may be possible to do more with less by making better use of new technologies, such as drones and cyber-defence, where costs are likely to fall over time.

But 2.5% of GDP is now too low.

3. Can we afford to spend more?

Unfortunately, the poor state of the UK’s public finances means that even reaching the new NATO target of 3.5% will be a stretch.

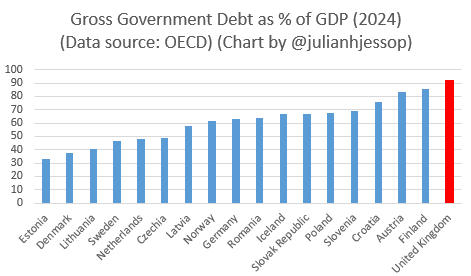

As my chart below shows, the Nordic and Baltic countries, as well as Germany and Poland, have much lower levels of government debt and are therefore both willing and able to increase defence spending more quickly. Their geographic proximity and, in many cases, their recent history, also makes them both more aware and more wary of the Russian threat.

In the UK context, it does help that more of the defence budget now counts as capital rather than current expenditure, which makes it a little easier to increase spending within the existing fiscal rules. But more borrowing is still more borrowing, whatever the purpose, and the markets are already nervous about the outlook for UK debt.

Nonetheless, defence is a textbook example of what economists call a “public good”. In particular, no one can be prevented from benefiting even if they fail to contribute to the cost. This means that even a government that is determined to reduce the size of the state should be willing to spend more on defence.

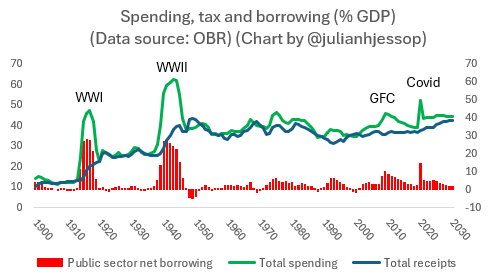

Finally, of course, it is hard to put a price on national security. But spending 3.5% of GDP on a credible deterrent is clearly preferable to the costs of the two World Wars, when government spending soared.

4. Are Brits ready to pay up?

Another characteristic of defence spending – especially on a deterrent – is that the benefits are not as tangible as spending on many other goods and services. In other words, there are difficult trade-offs involved.

The evidence from opinion polling here is a little worrying. Many surveys (such as here and here) show that voters support the general principle of strengthening the armed forces. But this is rather like asking people whether they are in favour of “motherhood and apple pie”.

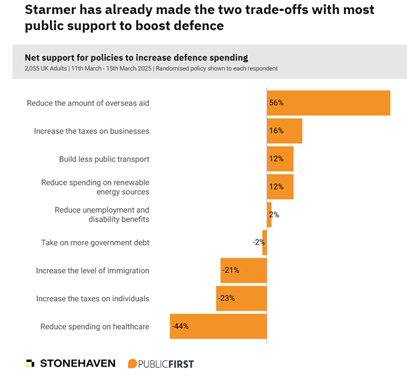

The problem is that support weakens markedly when people are invited to consider specific trade-offs, such as a straight choice between spending more on defence or on the NHS, or when the willingness to pay more tax to fund defence is tested. The chart below (source here) makes this point well.

More generally, there is a growing perception (reflected in the British Social Attitudes survey) that the levels both of government spending and of taxation are now too high. Are enough voters willing to make an exception for defence? I believe so, but this cannot be taken for granted.

5. How else can politicians make the case?

Politicians could make a stronger case for increasing defence spending by broadening the appeal, making this about the wider economic and social benefits as well as national security.

This is not the same as simply saying that more defence spending is “good for growth”. The overall impact on the economy would depend on how the additional spending is financed and on whether there is enough spare capacity to meet the additional demand.

Compared to public investment in, say, transport and housing, defence spending is less likely to increase the productive potential of the economy. More investment and more jobs in defence might then just mean less investment and fewer jobs elsewhere. Inflation and interest rates could be higher too.

A larger part of the defence budget might also be spent overseas, reducing the multiplier effects in the UK economy. However, increased spending by allies could provide more business for UK defence companies as well.

The regional impact could be a positive too. An increase in defence spending will probably favour regions outside London and the South East, helping areas with more military bases and which are more dependent on manufacturing than services.

These areas might also have more spare resources to divert to defence-related activities, including more people who would otherwise be unemployed, as ongoing de-industrialisation frees up more capacity in manufacturing and allied sectors such as steel production.

6. Where will the money come from?

The numbers are scary. Increasing defence spending by one per cent of GDP straightaway would cost around £32 billion in today’s money – equivalent to nearly four pence on the basic rate of income tax. Hitting the 3% target by 2029 would probably cost around £16 billion, or two pence on the basic rate.

Ideally, this increase would be funded instead by savings elsewhere in the government’s budget. This has already been done by cutting overseas aid. A future government might target savings on welfare spending and “green” projects, or roll back plans to splash more cash on an activist “industrial strategy”. In the meantime, though, the current government will probably have to rely on a windfall from lower interest rates, or choose to raise taxes even further.

7. Are there any short cuts?

Several ideas are being floated.

One is a new tax purely to fund additional defence spending. This could be modelled on the “Health and Social Care Levy”, a top-up to National Insurance proposed when Rishi Sunak was Chancellor. But like all such “hypothecated taxes”, this would largely be a gimmick and would complicate the tax system further.

Another option would be the issuance of new “defence bonds” (proposed recently by the Lib Dems). These could be similar to existing “green gilts”, or the saving schemes run during the two World Wars. Elsewhere, Germany now finances some defence separately through a constitutionally‑created special fund which allows borrowing outside the normal budget rules. However, as I noted earlier, more borrowing is still more borrowing, whatever the purpose, and Germany’s public finances are much healthier than ours.

There may also be scope for joint borrowing with the EU, pooling resources for defence spending and taking advantage of the lower cost of euro debt. This appears to be a key plank of the proposed UK-EU “reset”. But while Europhiles would love this, it would also open up a whole new can of worms, including less control over how the money is spent and all the risks as well as the benefits associated with sharing financial liabilities with other countries.

Crucially, none of these options would change the underlying economics. People would still be paying more tax, whether it is called a “Defence Levy” or something else. More borrowing to pay for defence would still crowd out other forms of saving and investment. There are no easy solutions here.

The bottom line

In short, raising defence spending will still be a hard sell. But, in my opinion, politicians must not shy away from the fight.

ps. you can follow me on X (formerly Twitter) @julianhjessop and on BlueSky. I also now post regularly on Substack.