One surefire way to harvest ‘likes’ on social media is to blame higher food prices on “greedy companies”. It is best to ignore the tediously repetitive posts from attention-seeking ‘engagement farmers’. But many people who might have some real influence are now pushing the ‘greedflation’ line too.

Most strikingly, Sharon Graham, head of the Unite trade union, recently made a direct link between the “38% jump in food prices” since 2020 and the “obscene” profits of £3.1 billion made last year by the retail giant Tesco.

The public is being asked to conclude that food prices would be much lower if the supermarkets were not so “greedy”. But that would suggest an alarming ignorance of the real world, let alone basic economics or elementary maths.

Margins matter

For a start, it is daft to bang on about how much money a company is making without comparing the figures to the size of the business, especially if accusing them of some form of bad behaviour.

To illustrate this, imagine two companies in different sectors. One is making profits of £500 million on sales of £10,000 million (a margin of 5%). The other is making much smaller profits of £100 million, but on sales of just £200 million (a margin of 50%). Which is more likely to be ‘profiteering’? (This might be even easier to answer if you imagine the first company is a food retailer and the second is flogging PPE.)

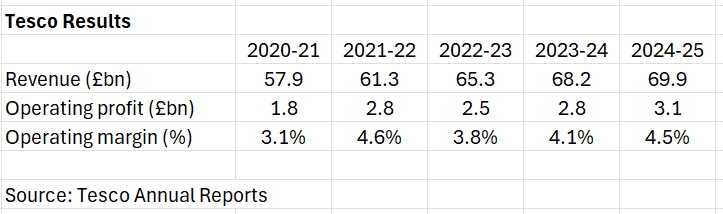

In this context, most people – even union barons – are surely aware that Tesco is a very large business. In order to generate profits of £3.1 billion last year, the company had to sell goods and services worth £69.9 billion. That is a profit margin of just 4.5%.

Moreover, these figures refer to ‘operating’ profits, before interest and taxes. Statutory post-tax profits were much lower, at £1.6 billion (or a margin of about 2.3%). That does not leave much to distribute to Tesco’s many shareholders, including UK pension funds and retirees, or run a sustainable business.

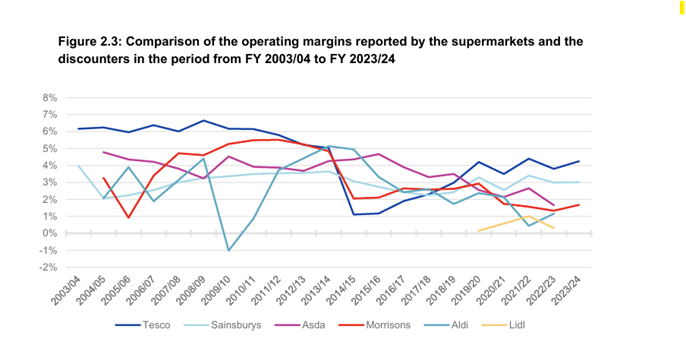

Indeed, profit margins are generally low across the UK supermarket sector, where a figure of around 3% is more normal. The chart below comes from a 2024 report by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), which found no evidence that shop price inflation was being driven by excess profits.

That is testament to the strength of competition, especially following the rise of discounters like Aldi and Lidl. In turn, this makes it practically impossible for any company in the UK to make super-normal profits from selling food.

Needless to say, these obvious points are still not enough for some people.

But isn’t any increase in profits unacceptable?

Many Tesco-bashers still like to point out that cash profits have increased in recent years and see this alone as evidence of ‘profiteering’.

It is common to compare percentage increases in profits with percentage increases in prices and to conclude, wrongly, that profits must be the key driver of inflation. This is more likely to be a mistake in low margin sectors where, crucially, profits only represent a small proportion of the final price.

Again, a hypothetical example may help. Suppose a company sells a basket of goods for £100 and makes a profit of £5 (a 5% margin). Some later it raises the price of the same basket to £150, with the increase broken down into a £45 increase in costs and a £5 increase in profits.

Just looking at the percentage increases, prices have risen by 50% while profits are up by 100%. Nonetheless, profits still only represent a small proportion of the final price (even in this example where margins have increased). The upshot is that the £5 increase in profits only makes a small contribution to the £50 increase in prices.

Put another way, even if profits had remained at £5, prices would still have risen by £45 (so by 45%, rather than 50%). And even if the company made no profits at all, prices would still have increased by £40 (or 40%).

Obviously, this is not an exact representation of what has happened in UK food retailing. But it shows why looking only at percentage increases in profits can be just as misleading as focusing on the headline numbers in millions (or billions) of pounds.

OK, but how can you defend a 75% increase in profits?

One often-quoted figure is that Tesco’s profits have risen by 75% between the financial years 2020-21 and 2024-25, much faster than the growth in sales of about 21%. But profits in 2020-21 were, of course, depressed by Covid, so this is not a good comparison. Comparing 2024-25 with 2021-22, profits have only risen by 11%, and margins are slightly lower.

It is true that Tesco’s cash profits are now at a record high, but you could say just the same about nominal wages. It makes far more sense to look at operating margins, and describing a figure as low as 4.5% as “obscene” is transparently ridiculous.

But even if Tesco made no profit all, any savings for customers would barely have made a dent in the 38% increase in food prices since 2020. This is because the increase in prices is almost entirely due to the pass through of higher costs, including the costs of agricultural commodities, transport, packaging, energy, and labour. (See the commentaries here from the Institute of Grocery Distribution, here from the Food and Drink Federation, and here from the House of Commons Library.)

But doesn’t low pay force Tesco workers on to benefits?

Another line of attack is that Tesco is somehow a bad employer (and even an ‘evil’ one). It is often claimed that “nearly 50% of its workforce are on Universal Credit, receiving about £600m a year.” This claim appears to have no foundation whatsoever and was debunked here by Reuters.

In any event, it is unrealistic to expect every employer to pay enough to ensure that every member of staff has no need to top up their income with benefits – regardless of their family circumstances, or the number of hours they work.

For example, suppose a single parent with two children – one disabled – works part-time for Tesco (or anyone else). Her pay is very unlikely to cover all her costs, so it seems perfectly reasonable to expect the government (i.e. the taxpayer) to top this up with benefits such as Universal Credit. It is simply not Tesco’s job to guarantee a minimum household income for all staff.

There are far bigger issues with Universal Credit, including the potential disincentives to work more hours. But again, supermarkets are not responsible for the design of the tax and benefit system.

But as it happens, most supermarkets, including Tesco, already pay above the statutory minimum wage. Indeed, hourly-paid workers at Tesco have had a pay increase of 32% since April 2022 (outpacing the national minimum).

Perhaps significantly, the main union at Tesco is Usdaw, not Unite. Usdaw’s take on the latest pay deal was more positive – noting that “hourly pay will exceed the Real Living Wage outside of London and continue to meet the new London Living Wage rates within the M25”.

With profit margins already low, the costs of any further large pay rises would have to be passed on to customers in the form of even higher prices. Jobs would probably go too as the company accelerated automation.

What about CEO pay?

Of course, like most businesses, the CEO of Tesco is paid far more than frontline staff (a ratio of 373:1, according to some reports).

But the economic reality is that the CEO has far more influence over the success or failure of a business than any individual worker. He (or she) would also be far harder to replace. For much the same reason, the footballer Erling Haaland is paid far more than the people who sell the scarves at Manchester City’s ground.

The bottom line

This all begs the question of why Sharon Graham – and many others – are so keen to pick on Tesco. I suspect it is simply because the headline numbers are bigger, giving a better soundbite to amplify the anti-capitalist message. But whatever the reason, it is depressing that so many opinion formers choose to lambast successful businesses rather than address the real issues.

I for one am entirely comfortable when a successful business manages to make a little more money, whether through expanding market share or efficiency savings, or even just as the reward for taking on more risk and helping to feed the nation during successive crises. If you think Tesco should not exist at all, feel free to tell that to the 330,000 employees, or just shop elsewhere.

I am also happy to leave the level of executive pay to the shareholders who are actually picking up the bill.

The problem of low wages cannot be solved by simply forcing companies to pay more, while ignoring all the trade-offs involved in making it more expensive to employ people. Nor would capping supermarket profits help to solve the problem of high food prices. But for some, it is so much easier just to blame “fat cat bosses”.

(Ps. for the many trolls out there, nobody is paying me to defend Tesco, and certainly not Tesco itself. But, for the record, I am a ClubCard holder.)