I first visited a food bank in 2017 at the invitation of the Trussell Trust, the admirable charity which runs the UK’s largest network of emergency centres providing food to people in crisis. Since then the use of their food banks has continued to grow rapidly, largely due to problems in the benefits system and the transition to Universal Credit in particular. I’m therefore happy to back the Trust’s #5WeeksTooLong campaign. But there are still plenty of misconceptions about the activities of food banks, and how to interpret the statistics in the context of wider debates about poverty.

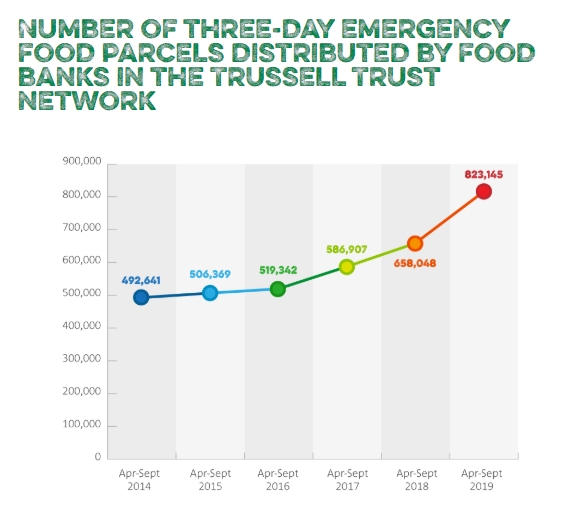

Let’s begin with the raw data. The Trussell Trust now supports food banks operating from more than 1,200 locations around the UK. Between April 2018 and March 2019, they distributed 1.6 million food parcels (including nearly 600,000 to children), an increase of around 19% on the previous year. What’s more, as the chart below shows, use of the Trussell Trust network has surged by 73% in the last five years.

The latest half year data shows this trend continuing. Indeed, the number of food parcels handed out between April and September 2019 was up 23% on the same period in 2018.

These figures are only a guide to the number of individuals who rely on food banks. In part this is because the same person may visit a food bank several times a year and therefore receive more than one parcel. In particular, someone using the Trussell Trust network takes, on average, two parcels over a twelve-month period. This means that the number of people using Trussell Trust food banks is only about half the number of parcels that this particular network hands out.

However, the Trussell Trust is not the only provider. Research from the Independent Food Aid Network suggests that the more than 1,200 centres in the Trussell Trust network account for roughly two-thirds of all emergency food banks in the UK. This implies that there are around 2,000 food banks in total, probably helping well over a million people in any one year. Indeed, the Trussell Trust’s own report, ‘The State of Hunger‘, suggests that as many as one in fifty UK households may have used a food bank in 2018/19.

These are depressing numbers, but it’s also worth putting both the level and growth rates of food bank use in the UK in some sort of context. I’ll start with the level. Many commentators have expressed outrage that even in one of the wealthiest countries in the world, so many people rely on food banks. Nonetheless, the current levels of food bank use in the UK would actually be considered normal in many other countries.

For example, a 2014 review found that there were around 800 food banks in Canada, serving 850,000 people every month; 1,000 food banks in Germany, helping at least 1.5 million people; and 2,000 in France, helping 3.5 million people.

In 2017, members of the European Food Bank Federation (FEBA) network provided food to more than 8 million people across Europe. And according to the Global FoodBanking Network’s 2018 report, the leading food bank network in Australia helps 652,000 people every month, including 176,000 children. In other words, the UK is not an outlier.

This is consistent with other evidence that poverty levels in the UK are unexceptional. Here, it is common to see headlines such as ‘14 million people in the UK live in poverty’. However, these figures actually refer to (relative) measures of income inequality, such as the percentage of people living with less than 55% of the median income, adjusting for factors such as housing costs and debt.

To be precise, the Social Metrics Commission estimated last year that 14.2 million people in the UK are in poverty on this definition (8.4 million working-age adults, 4.5 million children, and 1.4 million pension age adults). For example, the poverty threshold for the resources available to a childless couple, after paying for housing, is £252 a week (roughly £13,100 a year). For a couple with two children, one of whom is aged under 14, it is £408 a week (roughly £21,200). These are clearly very tight budgets, but not what most people would think of as ‘poverty’, or at least not ‘extreme poverty’.

What’s more, even on the basis of this very broad measure, levels of poverty in the UK are similar to those in other high-income countries such as Germany, New Zealand, Luxembourg, Australia and Canada. The OECD publishes comparable data on ‘poverty rates’, which it defines as the ratio of the number of people (in a given age group) whose income falls below the poverty line, taken as half the median household income of the total population. As the chart below show, the UK sits roughly in the middle of pack.

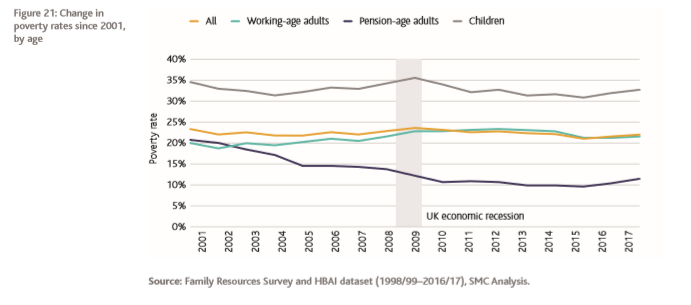

Nor has there been a major change in the UK over time. The chart below is from the 2018 Social Metrics Commission report. There are other more timely data and I will return to them in another blog, but the big picture is that relative poverty has been broadly stable.

I’d go one step further and suggest that the recent growth in use of food banks in the UK is partly a process of catch-up with other countries where food banks have long been a common means of providing benefits-in-kind. In the words of the Global FoodBanking Network (page 80 of their 2018 report), ‘the food bank model has been an effective hunger relief intervention for 50 years in industrialised, high-income countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and most of Europe’.

While the need for food banks isn’t obviously something to be proud of, their use in the UK shouldn’t be a source of national shame either. Indeed, many advocates of Universal Basic Services (a scheme which would provide a range of essential goods and services, at no cost, to anyone who wants them) have even suggested this could be extended to include some free meals.

There are some important caveats about the Trussell Trust data too, especially when making comparisons over long periods. Some of the increase in the number of people helped by the Trussell Trust will be due to the expansion of the Trust’s activities into new regions, or the replacement of existing local initiatives, rather than an indication of a surge in overall demand.

This is not a significant factor in the last six months, when the number of food banks run by the Trussell Trust has been relatively stable. But it has played a big part in previous jumps. For example, in 2009 the Trust operated in only 29 UK local authority areas. By 2013 this figure had leapt to 251. These new areas had presumably experienced food poverty before. It would clearly be wrong to conclude that nationwide poverty had increased by anywhere near the same amount.

The awareness of food banks is now greater too. This factor could have increased both demand and supply. For example, shoppers at leading supermarket chains are now able to donate food and other essentials for food banks to pass on to those in need, and many food banks have partnered with local companies.

In short, it would be completely wrong to conclude that the numbers of people in poverty have surged on the basis of the Trussell Trust data alone. It would be far more accurate to say that more people are now being helped by the Trussell Trust who might otherwise have relied solely on other forms of support, notably cash benefits provided by the government.

Equally, though, it would be misleading to claim that increased use of food banks in the UK is simply due to their increased availability. It’s a myth that people can just turn up at a food bank and walk away with free food. In the case of the Trussell Trust, professionals in the local community (such as doctors, health visitors or social workers) identify people in need and issue them with a voucher for three days’ food.

What’s more, there is still plenty of stigma attached to visiting a food bank (albeit perhaps less so than in the past). Indeed, some vouchers are never actually redeemed. And there is some evidence of unmet demand: four in five users of a Trussell Trust food bank reportedly go hungry multiple times per year.

What we can say with confidence is that food banks are acting as a stop-gap where government has failed. As I first found two years ago, it is impossible not to be impressed by the Trussell Trust and the dedication of its staff and volunteers. Indeed, the Trust appears to be delivering a much better service than many government agencies, with some truly joined-up thinking. For example, the ‘More Than Food’ initiative provides access to many other forms of help, notably support for people with mental health problems.

In summary, there is no doubt that the increased use of food banks has provided an early warning of serious problems in the timing of benefit payments. There are also widespread examples of maladministration, especially in the sanctions regime, which are contributing to poverty and hunger. This needs fixing. But is the use of food banks a peculiarly British problem? Absolutely not.

Indeed, levels of food bank use are similar in most high-income countries, and food banks are widely recognised as an effective way to help those in need. While food banks are now helping more people in the UK than ever before, this does not mean that the numbers in poverty have increased to anywhere near the same extent.

This raises some important question marks over Labour’s pledge to halve food bank usage in the UK within its first year of office and to end the need for them altogether within its first three years. It should be possible for any government, Labour or Tory, to reduce the demand for food banks by tackling the problems in the benefit system. However, ending their use altogether would almost certainly be counter-productive, even if it were realistic. Put it this way – why is the food bank model so widely used elsewhere? Does Labour think it can abolish poverty completely?

Labour has at least acknowledged that charitable food banks would have to be replaced by ‘different food security measures to be taken across several local and central government departments’. But would these alternatives work as well? Would it not be better to find other ways to help people lift themselves out of poverty, rather than yet more state intervention? I’m not convinced Labour has the answers.

In contrast, I think that tackling poverty requires a pro-market agenda. Instead of ever-higher transfer payments, why not focus on reforming the planning system to reduce housing costs, or cutting taxes whose burden falls disproportionately on the working poor, or promoting rather than penalising more flexible forms of employment? In the meantime, though, hats off to the Trussell Trust for filling in where government has clearly fallen short.

2 thoughts on “Should we try to do without food banks?”